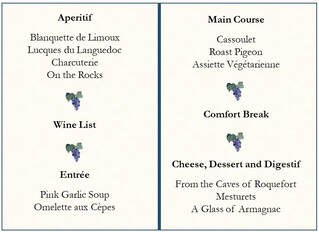

To give you a taste of this delicious book, I have selected two items from the menu: 'Blanquette de Limoux' and 'From the Caves of Roquefort'.

The first chapter is part of the aperitif, and we will visit the longest carnival in the world and establish the truth about the world’s oldest sparkling wine. For the cheese course, we will discover the history and legends of Roquefort and learn why the success of the cheese has turned its home into a ghost town. You can find more sample chapters on the Amazon website for your country of residence and, of course, you can buy the whole book for the complete gastronomic experience!