A family stroll through prehistory in the Pyrenees

Dolmen d’Els Pascarets, Eyne

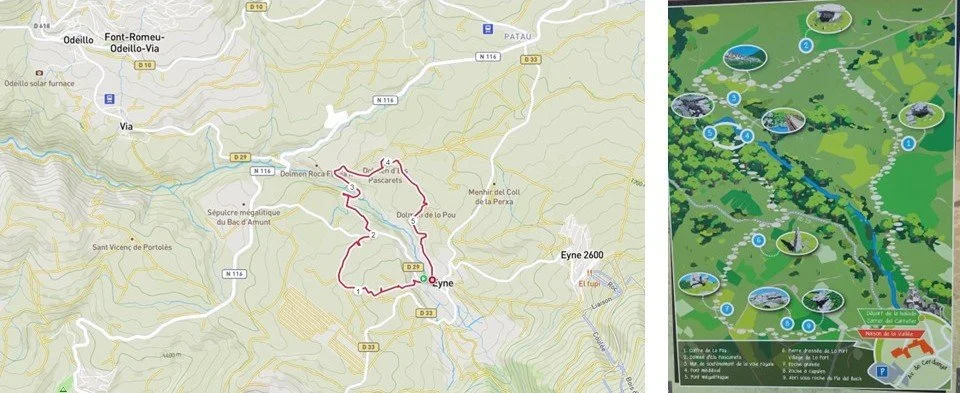

One of my favourite short walks in the Cerdagne is a five-kilometre balade néolithique, or Stone Age stroll, around the village of Eyne. As well as fine views of the Pyrenees, visitors of all ages will be astonished to discover such a wide range of ancient monuments in such a short distance. To help make sense of it all, the tourist office has erected a well-written and nicely-illustrated information board at each of nine stops along the route (the text is only in French and Catalan, I am afraid).

Having been around the circuit in both directions earlier this year while researching my forthcoming book, I recommend ignoring the tourist office’s numbering sequence. If you go clockwise, you will start with Number 9, but the exhibits make more sense. Here are a few of the highlights.

Number 9 is a natural rock shelter occupied briefly around 4000 BCE, and for a longer period around 1800 BCE. Number 8 is a rock as big as a car that has been pockmarked with cupules the size of a tennis ball cut in half, a prehistoric feature found on rocks across Europe. What were they for?

The cupules are often linked by a channel, and water will flow from one to the other, and so would blood if they were used for a sacrificial rite. Or perhaps they were designed to hold offerings to the gods, or salt for livestock, or were part of a celestial map or calendar, or maybe they were part of a game. No one knows.

Number 6 is a menhir of indeterminate age. A boundary marker? An assembly point? Whatever its purpose, during the Iron Age this menhir was at the centre of a village where houses of timber and clay were built on foundations of quarried granite.

From here, a gentle descent leads down to a Neolithic bridge, swiftly followed by a medieval bridge. On the far side of the river, a track known as The Royal Way climbs a steady gradient towards open countryside. Hannibal may have come this way with his 9,000 cavalry and 37 elephants. The Romans certainly did, and the road was probably improved under Louis XIV when France took control of this part of the Cerdagne.

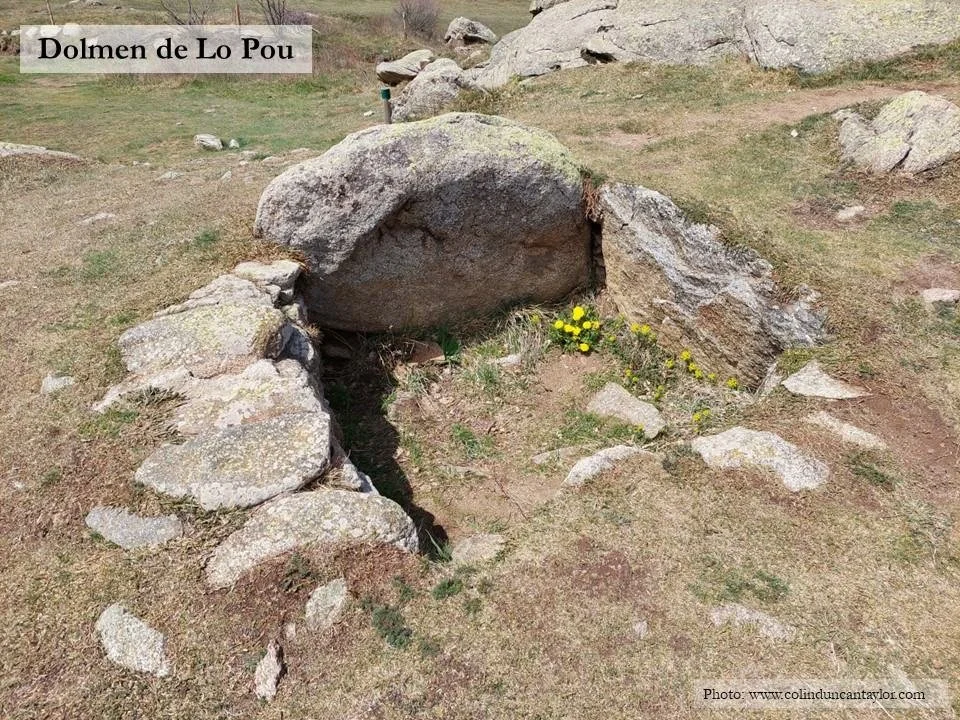

The Stone Age stroll finishes with two fascinating dolmens, or prehistoric tombs. The first is the most photogenic - the Dolmen d’Els Pascarets shown in the picture at the start of this article. Note that its capstone was only rediscovered in 1987 so what we see today is a reconstruction imagined by contemporary archaeologists.

The second dolmen, and the last stop along the route, offers an explanation for the absence of bones in so many Pyrenean tombs. Built around 2800 BCE, the Dolmen de Lo Pou would originally have enclosed a space of around one cubic metre. Inside, archaeologists discovered a smaller box made of flat stones, and inside that, they found burnt bones and fragments of pottery. It proved impossible to tell if these bones were of human or animal origin, although the latter seems more likely because human cremation did not become common practice in the Cerdagne until 1,500 years later. Whatever their origin, burning made the bones more resistant to the acidity of the soil. The reason so few skeletons have been found in tombs like this is that the bedrock is made of granite which tends to make the soil above it acidic, and in turn, the acidic soil eats away at bones and within a few decades, unburnt ones disappear. Poor archaeologists!

After a walk like this, it is easy to understand why making sense of prehistory has been likened to the challenge of doing a jigsaw puzzle where an unknown number of pieces are missing and where no one has ever seen the picture on the box.

The route is well-marked, but this GPX file may still be useful: Download GPX file