|

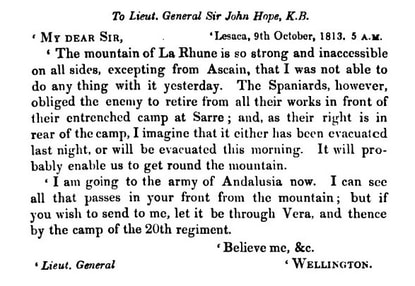

Small but challenging By Pyrenean standards, La Rhune is a modest mountain, but from its summit at 900 metres above sea-level, visitors can admire a 360-degree panorama. To the north-west, Biarritz and Saint-Jean-de-Luz on the Atlantic coast. To the south-west, Spain and the Bidasoa valley. To the east, the higher peaks of the Pyrenees. Climbing La Rhune is harder than many people expect. An ascent by any path involves a vertical height gain of over 700 metres, and proximity to the ocean can bring in thick wet clouds at a moment’s notice. Every year, the gendarmes and their helicopter rescue hikers who are lost, exhausted, injured and often ill-equipped. Meanwhile, 300,000 other visitors take a much easier way to the top, as we will discover. Legends and history of La Rhune Like many misty mountains, La Rhune has its legends. On its middle slopes, it also has more than its fair share of menhirs, cromlechs and dolmens from Neolithic times. Nearby, a star-shaped fort and other military defences were the scene of several days of fighting between the British and Spanish armies of Wellington and the French army of Soult in October 1813. After the first day of fighting, Wellington wrote, ‘The mountain of La Rhune is so strong and inaccessible on all sides, except from Ascain, that I was unable to do anything with it yesterday.’ These relics might attract a handful of history lovers, but what makes La Rhune the most-visited tourist attraction in the Pays Basque are the exploits of an energetic empress. A royal boost for tourism in the Pyrenees Eugénie de Montijo was born in Granada in 1826. When she was eight, a family holiday took her to Biarritz which in those days was nothing more than a simple fishing village. She swam off the beach of Port Vieux (just below the modern aquarium) and played with the local children. A few years later on another holiday, her mother took her to the Pyrenean spa town of Eaux-Bonnes, south of Pau. These two places became her favourite destinations, and a year after her marriage to the emperor Napoleon III, Eugénie persuaded her new husband to make the first of many long journeys to Biarritz. While he was there, Napoleon bought 15 hectares by the beach and set to work building a palatial home which he named the Villa Eugénie, but today is the luxurious Hôtel du Palais. Regular visits by the imperial couple attracted other royalty to Biarritz, including Britain’s Queen Victoria and Spain’s Alfonso XIII. Under the patronage of Eugénie, Eaux-Bonnes and other destinations at the western end of the Pyrenees also grew in popularity. An imperial expedition One day in September 1859, Eugénie had a new idea. Why not climb La Rhune? So off they went by charabanc, a royal party of 50, to the village of Sare at the bottom of the mountain’s eastern slope. Even an energetic empress was not prepared to climb to the top on her own two feet. Everyone took to mules instead, but this proved to be a delicate affair due to the use of a Basque curiosity: the cacolet. This resembled a couple of chairs hung off a plank over the pack animal’s back, an arrangement that required the two humans to be of equal weight, or balanced evenly by adding a few stones to one side or the other. On the way up the mountain, the royal party paused for a peasant’s picnic of cured ham, chilli omelette and almond-flavoured Basque cake (since then, Jambon de Bayonne and Piment d’Espelette have acquired gourmet status). This was at a spot known as Les Trois Fontaines, close to the fortifications fought over by Wellington and Soult in 1813, and only half-way to the top. After lunch, there was dancing, and energetic Eugénie joyfully took part in a fandango. Exhausted travellers When the intrepid travellers resumed their ascent, Eugénie took the lead and encouraged her companions, but some members of her party were flagging. Nineteenth century ladies rarely climbed mountains, even on the back of a mule, and the Countess de la Bédoyère suddenly burst into tears and exclaimed, ‘Just leave me here to die!’ So Eugénie ordered her guides to make stretchers and carry the countess and a few other exhausted noblewomen up the mountain. The empress was first to reach the summit and she jumped off her mule so quickly, she almost unseated her companion balanced on the other side of the cacolet. But it was too late to linger and admire the magnificent views. The exhausted party set off down the path towards Ascain which Wellington had identified as the easiest route 46 years earlier. They reached the village at 22.00, and a grateful empress made a generous donation which helped restore the local church. Etched in local memory Understandably, this adventure also made a strong impression on the local people. The following year, the commune of Ascain erected a 5-metre-high commemorative obelisk near the summit which you can still admire today. Let the train take the strain Eugénie repeated her exploit in 1862, this time in the company of her husband. More and more visitors followed the imperial example until, in 1908, someone had the idea of making the summit accessible to all. Work on a rack-and-pinion railway began in 1912, was interrupted by the First World War and completed in 1924. Since then, wooden carriages have carried millions of tourists to an increasingly crowded top. The border runs over the summit, with the railway station and a telecommunications tower on the French side, and three bar-restaurants on Spanish territory. Pottok ponies When I made my own ascent in September 2023, I followed a similar route to the one taken by empress Eugénie 164 years earlier, but without the picnic and fandango. Along the way, I encountered several hundred other people who were travelling under their own steam. Almost as numerous were the horses, an ancient breed called the Pottok, a word which means ‘little horse’ in Basque. My wife, in contrast, took the train because of a sporting injury, and this taught us a lesson which allows me to offer some advice. To avoid a long wait, book ahead, but check the weather forecast because tickets are not refundable or exchangeable. For maximum flexibility, follow my GPX track.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Colin Duncan Taylor"I have been living in the south of France for 20 years, and through my books and my blog, I endeavour to share my love for the history and gastronomy of Occitanie and the Pyrenees." |

||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed