|

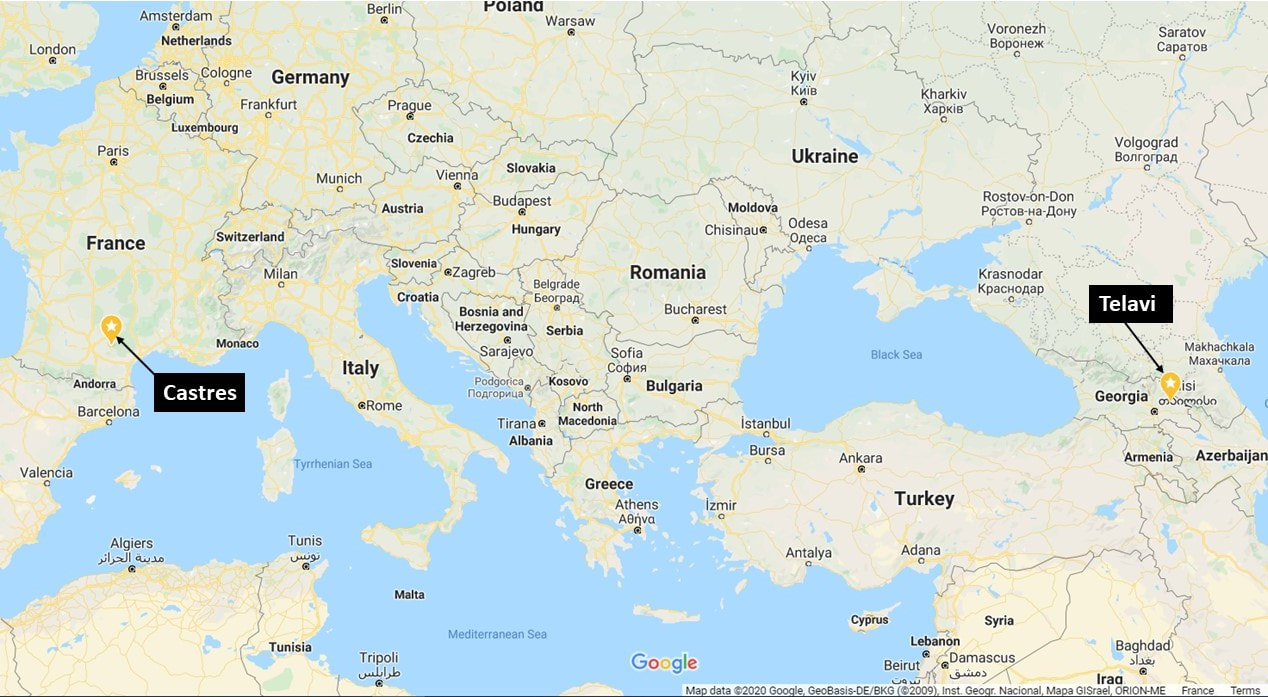

This post tells the extraordinary story of Vakhtang Sekhniachvili, and it follows on from my previous post of 11 January in which I visited the archives in Albi on a quest to identify a pair of dead German soldiers. FOLLOW THIS LINK IF YOU WANT TO READ THE PREVIOUS POST FIRST: who-were-the-two-dead-soldiers.html During my visit, another document caught my eye. Dated October 1944, it listed the names of ten German soldiers killed and buried within the commune of Castres during the Occupation. What intrigued me were their bizarre names and even stranger places of birth: Georgia, Mongolia, Turkestan, Kyrgyzstan and the Caucasus What, I wondered, were men like these doing in the German army? I went in search of answers and soon came across various articles about one of these men: Vakhtang Sekhniachvili. Born in the village of Telavi in Georgia in the Caucasus, he was conscripted into a Soviet armoured regiment in 1941. A year later, his tank was hit while fighting in the Ukraine. He survived but became a prisoner-of-war (POW). More than three million Soviet POWs are believed to have died in German custody – that’s around half of the total. Their deaths were caused by a combination of starvation, exposure, disease and executions. Vakhtang was among the several hundred thousand who chose to escape the deadly prison camps by joining the Wehrmacht. He was drafted into a unit called the Georgian Legion, and he was sent thousands of kilometres across Europe to Castres. By 1944, a large proportion of the ‘German’ troops occupying south-west France were ex-POWs like Vakhtang. They were known as Hiwis – an abbreviation of the German word ‘Hilfswilliger’ or auxiliary volunteer. They numbered around 600,000 in total, and the entire garrison of Castres consisted of Soviet POWs, apart from some 70 officers.

On 7 July 1945, he was awarded the French Military Cross and offered a post in the 1st Army under General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny. Understandably, he chose instead to return to his home village of Telavi where he proudly displayed his French medals and was treated as a hero. For a while, even the authorities were impressed: he was promoted by the Communist party and put in charge of propaganda. Then came the Cold War and Stalin’s purges. In 1947, Vakhtang was arrested by the KGB in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi, accused of being an imperialist spy, and of collaborating with the British and Americans. Pronounced guilty, his medals were confiscated and he was sent to the gulag. Most of the returning Hiwis met a similar fate or were executed. This period of forced labour lasted until Stalin’s death in 1953. Vakhtang was one of the first to be liberated, and many more of the surviving Hiwis found freedom under a general amnesty granted by Nikita Khrushchev in 1955. Despite his new-found freedom, Vakhtang yearned for two more things: he wanted to visit France one more time, and he wanted his medals back. His first wish came true in 2003. At the age of 82, he revisited his former area of operations on a trip funded by the French Ministry of Defence and the Conseil Général du Tarn. Then, at a ceremony in Tbilisi in July 2006, he became the first Georgian to be awarded the French légion d’honneur. Photo credits: thank you, Pierre Kitiashvili, for supplying the two photos. Pierre lives in Georgia, and his grandfather was the man on the motorbike in the first photo.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Colin Duncan Taylor"I have been living in the south of France for 20 years, and through my books and my blog, I endeavour to share my love for the history and gastronomy of Occitanie and the Pyrenees." |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed