How Wellington finally laid his hands on Napoleon’s greatest general

My recent posts about Marshal Soult and the Battle of Toulouse have unearthed a memory: in 2018, I enjoyed the rare privilege of being given a guided tour of Soult’s home town, including the house where he was born, the château which he built and where he died, and the mausoleum where he is buried. I have also remembered a tall story I was told during my visit about an unexpected encounter with Wellington.

As for calling him Napoleon’s greatest general, if one includes success in the world of politics – such as serving as prime minister, foreign minister and war minister under various monarchs, and founding the French Foreign Legion – Soult has no equal.

Fighting for his country, whoever was in charge

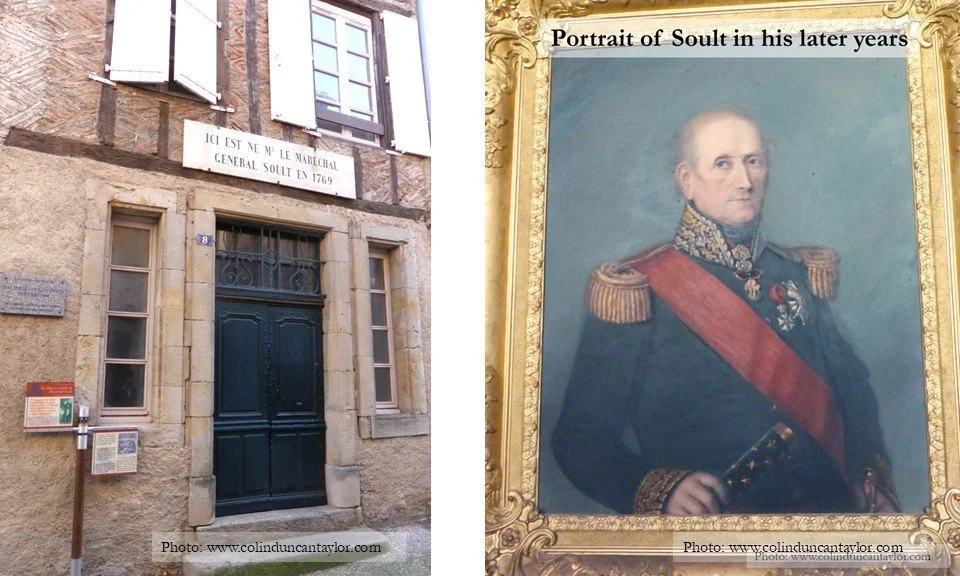

Jean-de-Dieu Soult was born in 1769 in the village of Saint-Amans-la-Bastide, but you won’t find it on the map. You will discover why at the end of this article. At 16, he joined the army of Louis XVI. After the Revolution of 1789, he rose rapidly through the ranks of the revolutionary army, and when Napoleon crowned himself emperor in 1804, Soult was among the first 14 marshals of the empire. He played a decisive role at Austerlitz and, from 1809, spent most of the next five years fighting Wellington on the Iberian Peninsula, then in southern France and finally at the Battle of Toulouse in 1814. Once he had signed the armistice with Wellington at the Seuil de Naurouze, Soult returned to his home in Saint-Amans-la-Bastide. A week or two later, he went up to Paris.

Lieutenant George Woodberry – a young British officer who fought at Toulouse – noted in his journal on 15 May 1814: ‘Marshal Soult is under arrest in Paris; they say he knew of Bonaparte’s abdication and the state of affairs in Paris three days before the Battle of Toulouse and he could have avoided it.’

Soult was soon exonerated, and one month later he was serving Louis XVIII as minister of war! When Napoleon returned to France the following year, Soult issued an order to the army in which he denounced Bonaparte as an usurper and an adventurer. Within weeks he was serving as Napoleon’s chief of staff, and fought alongside him at Waterloo.

From political exile to founder of the Foreign Legion

When Louis XVIII was restored to the throne, even Soult’s political skills couldn’t save him from exile. But after four years in Germany, he was allowed to return to France where Louis XVIII restored him to the rank of marshal. Charles X awarded him a peerage and Louis-Philippe made him minister of war. As part of his plans to expand the army, Soult created the Foreign Legion in 1831. By this time, he had also begun a construction project in his home town. His wife’s maiden name was Berg, and their new home became the Château de Soult-Berg. It was completed in 1835.

Queen Victoria’s coronation

In 1838, Louis-Philippe chose Soult to be his representative at the coronation of Queen Victoria in London. As far as I can determine, Soult and Wellington never met face-to-face during all the years they spent fighting each other in Portugal, Spain, France and Belgium. But according to the tale I was told during my visit to Soult-Berg, this long-overdue encounter took place at the time of the coronation. Supposedly, while Soult was at a banquet, Wellington crept up behind him, grabbed his shoulders and cried, ‘I’ve got him, by damme; I’ve found you at last, Marshal Soult!’ And the next day, the two men rode around London in a carriage admiring the sights and receiving rapturous applause.

I had always doubted this story until I came across a piece in the 3 July 1838 edition of the French daily newspaper La Quotidienne, written by its London correspondent two days after the coronation.

Two old enemies come face-to-face

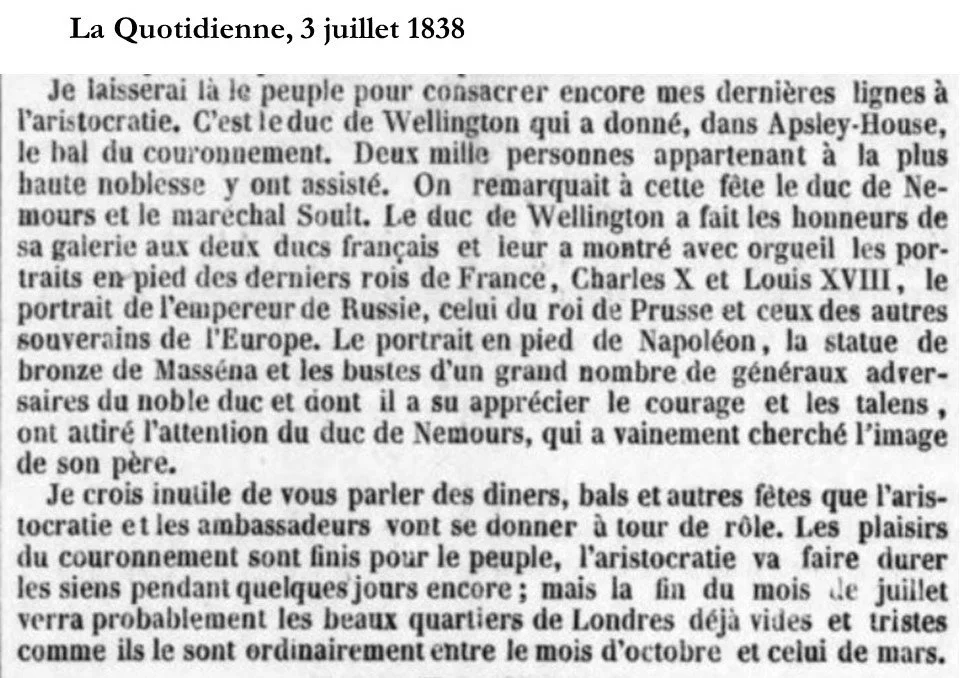

According to this article, once the newly-crowned Victoria had returned to Buckingham Palace, the festivities began, and the Duke of Wellington held a Coronation Ball at his Apsley House home. Soult was among the 2,000 guests, and Wellington proudly showed him his art collection which included busts of many of the generals he had fought against, and portraits of Napoleon, Louis XVIII, Charles X and many other European sovereigns.

Although there is no mention of the two former foes taking a carriage ride together, the idea of Soult receiving rapturous applause from the public is believable. According to Nicole Gotteri’s authoritative and monumental biography of Soult, this visit to London was among the highlights of Soult’s career, one of his most glorious campaigns. At the age of 69, a man who had spent so many years fighting the British was treated like a hero, received too many invitations to accept, visited the main sights in London, made trips to Windsor, Liverpool and Manchester, and hosted a ball in his ambassadorial residence where 1,000 high-society guests danced until five in the morning.

The Château de Soult-Berg

When Soult returned to France after this triumphal visit, Louis-Philippe appointed him foreign minister. Soon after, he added the role of prime minister, and at various times during the next seven years he also held the post of war minister. In 1847, Soult retired from politics and returned to his home at the Château de Soult-Berg. One of his first acts was to order the construction of a grand mausoleum attached to the parish church. On 26 November 1851 he died at home and was buried in this neo-classical tomb where the highlights of his career as a soldier and a politician are engraved in white marble. Shortly before the day of Soult's funeral, the town honoured its most famous son by changing its name to Saint-Amans-Soult. It lies ten kilometres east of Mazamet, in the department of the Tarn and in the shadow of the Montagne Noire.

Note: both photographs of painted portraits were taken inside the Château de Soult-Berg.