The secret of pastel, or how to turn a green plant into blue and gold

Between 1460 and 1560, the merchants of Toulouse became extraordinarily rich thanks to a plant called isatis tinctoria. In the city, they built magnificent mansions, and in the surrounding countryside new châteaux and dovecotes sprang up and village churches were rebuilt or extended.

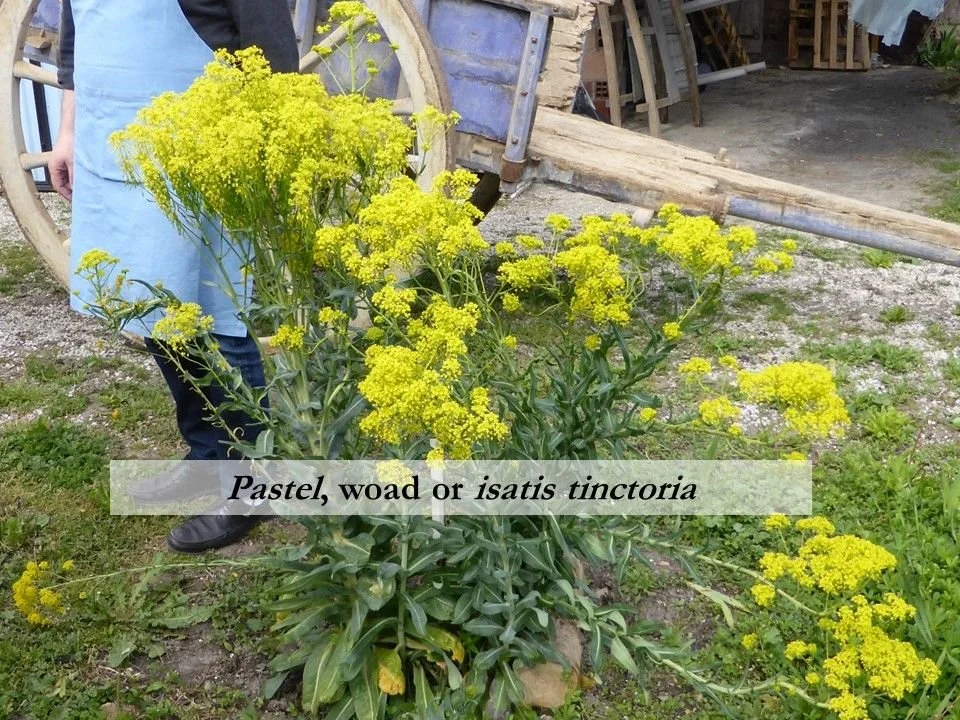

Pastel, woad or isatis tinctoria

In English, isatis tinctoria is commonly known as woad. In Toulouse it was pastel, derived from the Latin word for paste. It comes from the same family of plants as mustard or rapeseed, and from a distance it could easily be confused with other brassicas. Multiple stems rise waist high from a clump of dark green leaves at the base. At the top of the stems are clusters of tiny bright yellow flowers, but these were of no interest to the pastel merchants. The gorgeous blue colour of woad resides in the oblong-elliptical foliage at ground level.

Extracting the blue dye from these green leaves was a long and complicated process which started with grinding them into a pulp. But before that, the peasants had to cultivate the plants, and that too was a demanding task.

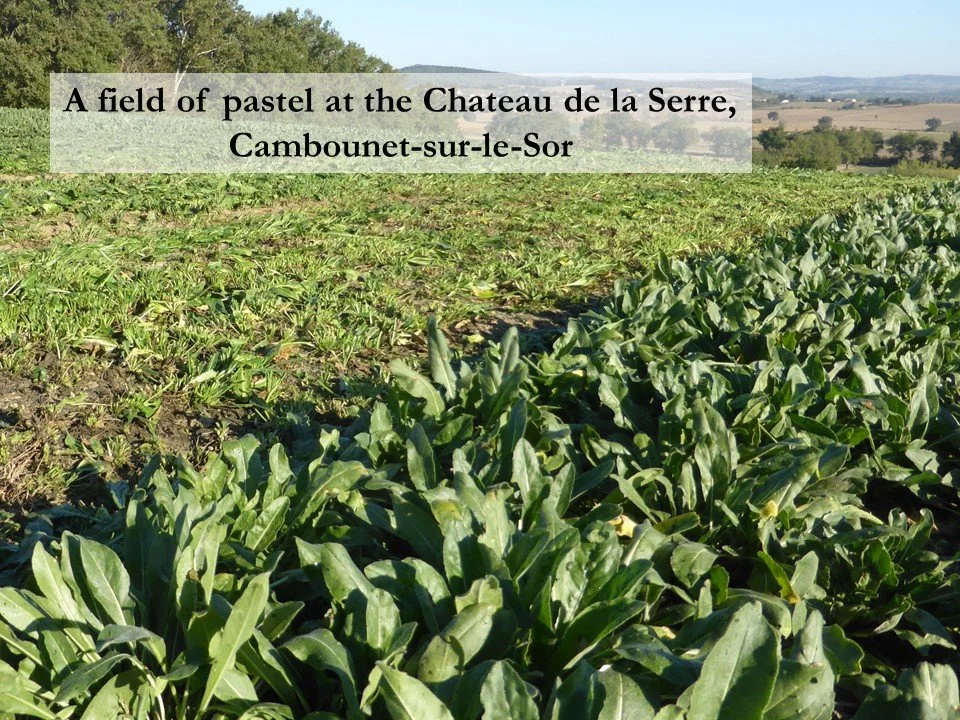

Toulouse – the most productive region for pastel

Although pastel was grown all over Europe, the area around Toulouse was exceptionally productive. In Thuringia, which was an important area of pastel production in central Germany, there was one harvest a year. Around Toulouse there were up to six, and the quality was among the best, largely thanks to the climate. The brighter the blue of the skies under which the plants grew, the brighter the blue of the dyes they produced.

The cycle of pastel cultivation

Half a dozen harvests between mid-June and early November made it a profitable crop, but an exhausting one for the peasants. They ploughed in the winter, planted in February or March, and then spent the next six months hoeing and weeding and harvesting. Growing pastel consumed huge quantities of labour, particularly those who were cheap to hire such as women, children and paupers in search of daywork.

Harvesting and processing pastel

During each of these multiple harvests, the pastel pickers took their baskets of leaves to the nearest water course to wash them. The peasants then spread out the clean leaves to dry, and within hours they took them to the pastel mill for grinding. Unlike wheat, pastel could not wait for a windy day; the leaves had to be processed immediately or the colour was lost, and the hydrography of the area was unsuited to water mills. Most of the pastel mills used bovines or equines to turn their millstones.

After crushing the leaves, as much liquid as possible was drained from the paste which was then formed by hand into balls called cocagnes. These were placed in racks in a well-ventilated area sheltered from the rain and left to dry for several weeks. Once the cocagnes were dry, they were stored until the end of the season. Until then, everyone was too busy weeding and hoeing and picking the next harvest to have time to work on the least pleasant stage of production.

It took four months of smelly work to transform the cocagnes into a product which could be shipped and sold to the textile industry. Early in the New Year the cocagnes were taken back to the same mills where the same beasts turned the same millstones. The ground-up cocagnes were then mixed with impure water, and the mushy mass began to ferment, usually on the brick-paved floor of the pastel-maker’s workshop where it was easier to stir or turn with a shovel. For several weeks the unpleasant mixture festered away and gave off noxious and revolting fumes. It took skill to control this process. The fermentation had to be lively enough to oxidise the glucose in the leaves and make them release their pigment, but if it went too far, there was a risk of destroying the colour. Adding human urine was the simplest way to speed things up, and cold weather or adding pure water slowed it down. The pastel-maker’s art lay in striking the right balance to obtain a product of the highest quality. Once the fermentation was finished, the paste was left to dry and then it was broken up to form something like fine gravel. The granules were very dark – almost black – and the first sacks of this agranat were ready for sale in May.

Exporting to international markets

Between August and October much of this agranat was shipped down the Garonne from Toulouse to Bordeaux, and in November and December ocean-going vessels took it to England or Holland. Another important trading route led to Spain where pastel from Toulouse supplied Castile’s textile industry.

When the dyers were ready to start work, the agranat was turned into powder and another complex process began, varying with the type of fabric to be dyed.

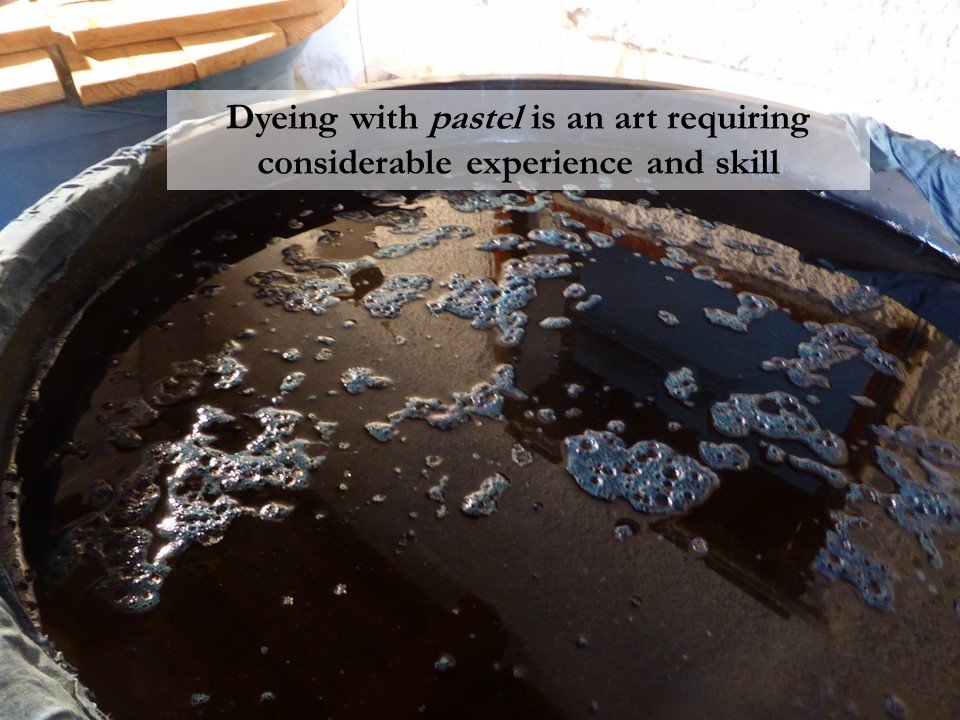

The renaissance of pastel dyeing

Despite its long history, little was written down about pastel. When, in the 1990s, an American-Belgian couple called Denise and Henri Lambert decided to bring pastel dyeing back to life, they worked with the School of Chemistry in Toulouse to perfect a new process that is over a hundred times quicker than the medieval method. The pigment can be extracted from the pastel leaves in less than a day, but using it to dye successfully is still an art requiring considerable experience and skill.