Transhumance: the long walk home

The longest walk

The Iriberri family claims that in France today, theirs is the longest transhumance anyone makes on foot. I joined them on the 3 and 4 September for the start of their 2022 odyssey. They will arrive at their farm in the tiny village of Labescau between Agen and Bordeaux on 25 September after a walk of around 300 kilometres with their 350 sheep, six dogs, Geronimo the donkey and a posse of friends.

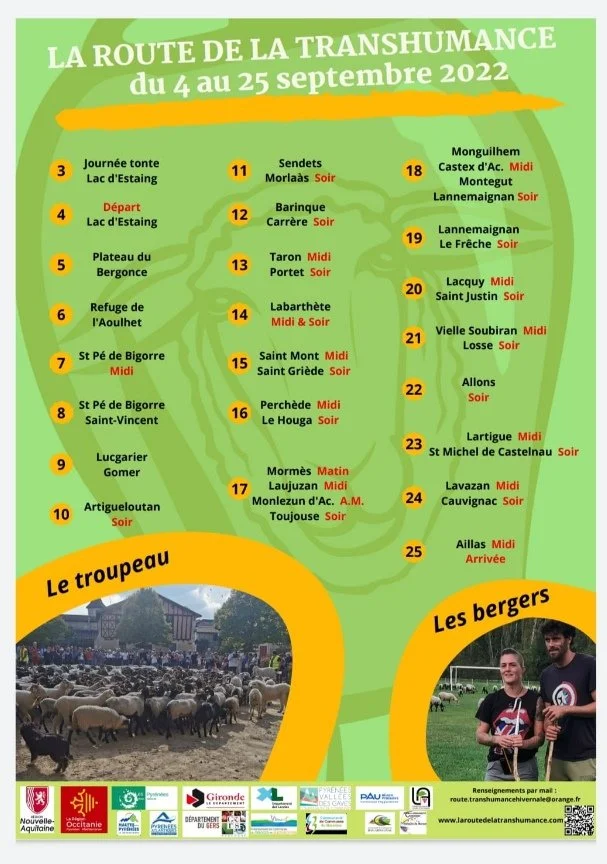

Here is the programme if you want to catch up with them along the way. Otherwise, they will be doing the same thing at the same time next year.

On my first evening at Lac d’Estaing (25 kilometres south-west of Lourdes), I sat and chatted with Pauline Iriberri who was relaxing in a camp chair after a hard day spent overseeing the shearing of her sheep in preparation for their long march across the hot plains of south-west France.

Shepherds with altitude

She and her husband Txomin (pronounced show-min) went up the mountain with their animals on 25 June and spent ten weeks living at 2,000 metres in a primitive shepherd’s hut with no running water, no electricity and no phone network while their sheep enjoyed the high mountain pasture. The humans lived off three loads of supplies helicoptered up to their hut the day before their arrival, supplemented by fresh provisions carried up the mountain by Geronimo every two or three days.

The origins of transhumance

The word transhumance derives from two Latin words meaning across (trans) the ground (humus), and more precisely, it refers to a form of mobile livestock husbandry in which herders move their flocks regularly and repeatedly between defined seasonal grazing areas. It is still practised in many parts of the world today, but it is particularly prevalent around the north side of Mediterranean basin from Turkey to Spain, and this is probably the route by which it was introduced to the Pyrenees around 7,000 years ago.

After that, there was little discernible change in the life of a traditional shepherd in the Pyrenees until motorised transport appeared in the 20th century. By around 1970, most farmers practising long-distance transhumance had switched to using lorries, although the last stage of the journey into the high mountains was still made on foot for reasons which will be obvious to anyone who has climbed up there themselves.

An ancient tradition reborn

In the late 1990s, a countryside heritage organisation called ADIPP based in Bordeaux decided to make an educational film about transhumance. Understandably, they did not want to point their cameras at livestock flying down the autoroute in trailers pulled by trucks. They wanted to capture the drovers and their beasts ambling through the picturesque countryside of southern France on their own four hooves or trotters. The problem was, no one had practised transhumance by foot between the department of the Gironde and the Pyrenees since the second world war.

To develop its film project, ADIPP teamed up with Pauline’s father-in-law, Stéphane Iriberri. He had been trucking his sheep back and forth to their summer pastures in the Pyrenees for ten years, but like many shepherds, he dreamed of doing it the old way. The main challenges were finding a suitable route away from modern traffic, and obtaining the necessary authorisations from the two regions and several departments through which they would have to pass.

In September 2000, Stéphane Iriberri walked back home from the Pyrenees with his 200 ewes. After that, he repeated his exploit every year until covid-19 appeared. He has now retired, although he made a guest appearance while I was at Lac d’Estaing. Txomin and Pauline have taken on the task of perpetuating this ancient tradition.

Starting with Stéphane’s first journey in 2000, ADIPP and the Iriberris have turned each stop along the way into an opportunity to educate children and adults, and to celebrate. Today, villages along the way are impatient to welcome the woolly, four-legged procession, and many of them organise a fête, including meals for several hundred diners.

‘Every day there is a celebration at lunchtime and another one in the evening,’ Pauline told me. ‘It can be rather tiring.’

Her smile suggested she was relishing this new challenge. And who wouldn’t, after spending ten weeks up a mountain chasing sheep?