The ruins of Liantran: discover one of the oldest pastoral settlements in the Pyrenees

At the start of September, I visited one of the oldest pastoral settlements in the Pyrenees, surveyed by archaeologists for the first time in 2018. From the Lac d’Estaing, south-west of Lourdes, reaching Liantran involves an eight-kilometre hike up the valley, plus 700 metres of climbing. By Pyrenean standards, the paths are good.

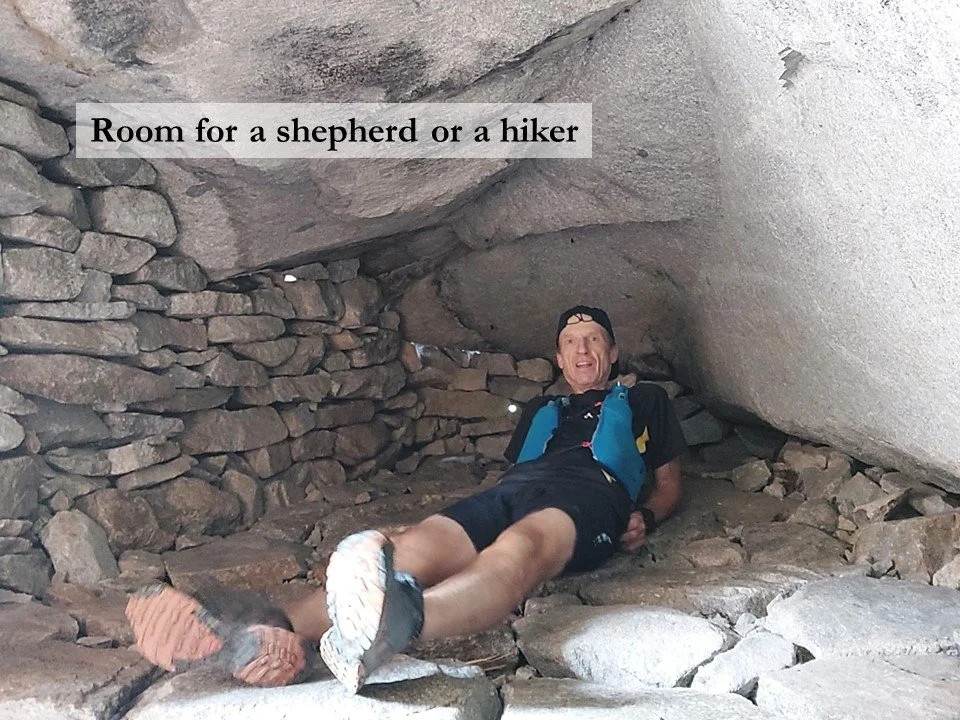

La Toue de la Cétira shepherd’s shelter

There is a bar-restaurant at the head of the lake, so I drank a cup of coffee and set off into the mountains. Five kilometres after leaving the head of the lake, I paused to inspect a quaint shepherd’s shelter restored in 2018. Called La Toue de la Cétira, it was created by adding a section of dry-stone wall beneath the overhang of a large boulder. Inside, it is large enough to allow a shepherd and shepherdess or a couple of hikers to shelter for the night.

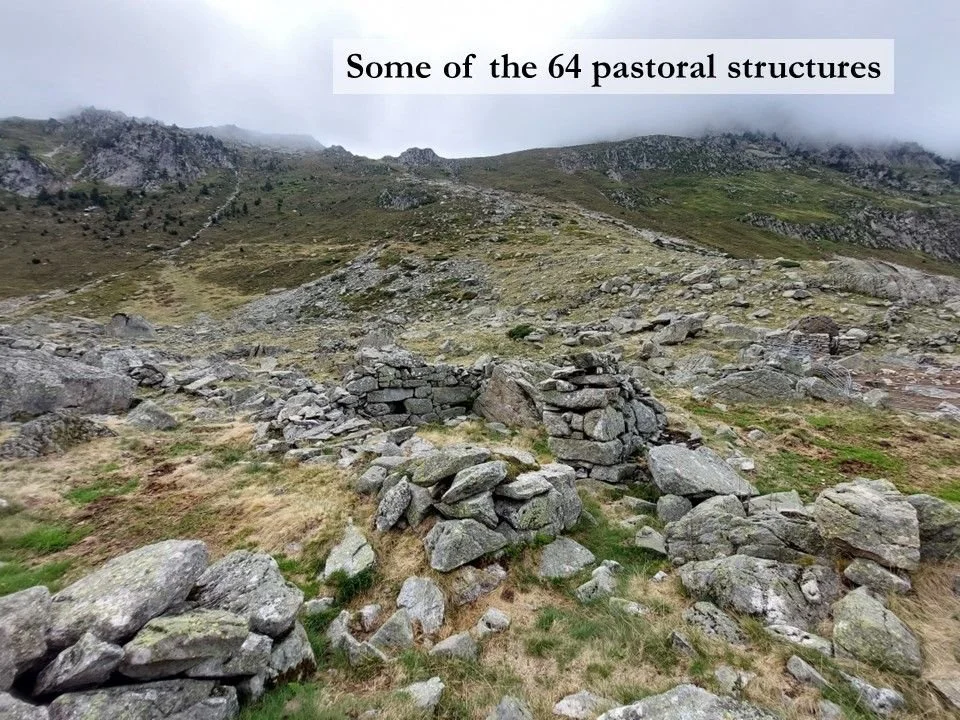

The ruins of Liantran

Three kilometres further up this increasingly desolate valley, I came to the ruins of Liantran. These are at an altitude of 1,824 metres, but the surrounding mountains are much higher. A little further, the land drops gently towards several small lakes.

One of the largest and most complex pastoral sites

Liantran has been used by shepherds for around 7,000 years, and it was surveyed by archaeologists for the first time in 2018. Using a variety of remote sensing instruments carried by a drone, they identified 64 structures, all built from stone, covering an area of around three hectares. This makes Liantran one of the largest and most complex pastoral sites discovered in the Pyrenees, and its archaeological remains include traces of 30 enclosures, eight cabins, three milking areas and seven niches which would have been used to conserve ewe’s milk.

From ground level, it is difficult to appreciate the scale of this settlement. A couple of the sheep enclosures are easily identifiable, and in one area, sections of galvanised steel livestock panels sealed the gaps between boulders and dry-stone walls to make a sheep pen.

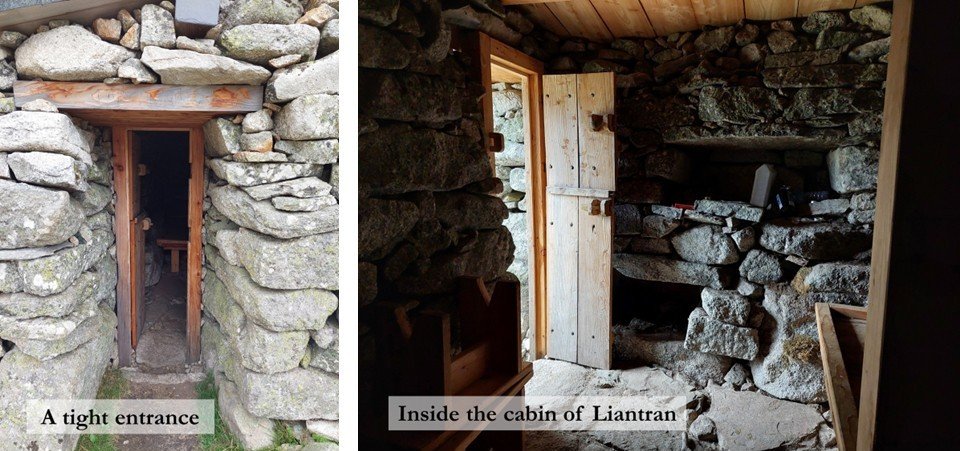

A traditional shepherd’s cabin

Then I spotted further proof that shepherds still live here in the summer months: a cabin dug into the hillside and half-buried by rocks (the first picture in this post). The stone walls are centuries-old, but the roof was restored in 2019 and topped with a layer of turf. The entrance is so narrow, even I had to turn sideways to reach the door. Inside, a wooden platform serves as a double bed.

Please close the door!

In an earlier post - The long walk home - I wrote about Txomin and Pauline Iriberri, a couple of shepherds who still practice long-distance transhumance on foot between Bordeaux and the Pyrenees.

I interviewed them down by Lac d’Estaing the day after they had vacated their own cabin after a summer sojourn of ten weeks. Should you be feeling energetic, retrace your steps for a kilometre until you reach the modern concrete cabin at the Plaa de Prat, turn right, and follow the footpath that climbs to a height of 2,000 metres where you will find La Cabane des Masseys. This is where the Iriberris spent their summer, and it offers the luxury of a window and an indoor fireplace.

Many cabins like these are occupied by shepherds during the summer months, but at other times of the year they can be used by hikers. Please remember to close the door when you leave!

If you are GPS-equipped, you may like to download this GPX file for the route.