Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 1 - Grotte d’Aurignac

Occitanie has played a central role in our understanding of prehistory, and Ariège boasts more prehistoric caves than any other department in France. Over a period of several months last year, I visited several of the ones that are open to the public. The prehistorians who were involved in the discovery or interpretation of these grottes were in many cases the same internationally renowned experts who explored even more famous caves which lie just outside my region (Lascaux, Les Eyzies and the Grotte de Chauvet, for example). They included people like Émile Cartailhac who, in 1882, took up a post at the faculty of science in Toulouse and became the first academic in France to teach prehistoric archaeology. And a young priest called Henri Breuil who, over the next 60 years, would become even more influential than Cartailhac. And more recently, Jean Clottes, the man who was called upon to assess the Grotte de Chauvet when it was rediscovered in 1994.

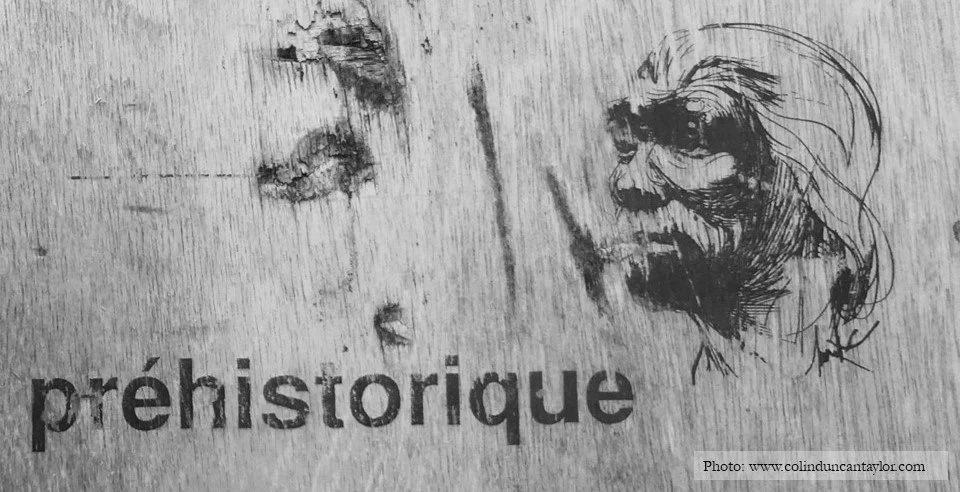

Grotte d’Aurignac

The village of Aurignac lies 60 kilometres south-west of Toulouse and the eponymous cave is 500 metres to the west of town beside he main road. In Aurignac itself, there is a large and modern interpretation centre which provides an excellent overview of prehistory in general. The cave and the centre are connected by a footpath.

Aurignac is an unpretentious cave barely the size of my garage, but it has played an outsized role in the development of prehistory as a scientific discipline. In 1860, an amateur scientist called Edouard Lartet found human remains and tools inside this cave along with the bones of various extinct animals such as the cave bear and woolly rhinoceros. These discoveries, combined with others he made in the Dordogne, led Lartet to conclude that modern humans must have been living in Europe long before anyone had suspected. It took a few more years for his ideas to be accepted, but eventually his discoveries at Aurignac were recognised as examples of the oldest modern human culture in Europe, subsequently named Aurignacian, and covering the period between 43,000 and 26,000 years ago (these dates vary slightly in different parts of Europe).

There is little to see at the cave itself, but if you go there after the interpretation centre, you will find it a pleasant place to reflect on what you have learned about our distant ancestors. At the time of my visit (June 2022), I was lucky enough to meet a team of young archaeologists who were busy excavating the bank a few metres to the left of the cave in search of more prehistoric evidence.

FOLLOW THESE LINKS TO READ OTHER SECTIONS OF THIS POST:

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 2: Grotte de Niaux

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 3: Grotte de Bédeilhac

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 4: Grotte de Gargas

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 5: Grotte de Mas d’Azil

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 6: Caune de l’Arago and the Tautavel museum of prehistory