Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 4 - Grotte de Gargas

Occitanie has played a central role in our understanding of prehistory, and Ariège boasts more prehistoric caves than any other department in France. Over a period of several months last year, I visited several of the ones that are open to the public. The prehistorians who were involved in the discovery or interpretation of these grottes were in many cases the same internationally renowned experts who explored even more famous caves which lie just outside my region (Lascaux, Les Eyzies and the Grotte de Chauvet, for example). They included people like Émile Cartailhac who, in 1882, took up a post at the faculty of science in Toulouse and became the first academic in France to teach prehistoric archaeology. And a young priest called Henri Breuil who, over the next 60 years, would become even more influential than Cartailhac. And more recently, Jean Clottes, the man who was called upon to assess the Grotte de Chauvet when it was rediscovered in 1994.

Grotte de Gargas

The Grotte de Gargas lies in the foothills of the central Pyrenees south of the A64 between Saint-Gaudens and Lannemezan. When humans lived here between 28,000 and 24,000 years ago, there were two separate caves, each with its own small entrance. In the 19th century, someone decided to connect them by a tunnel for reasons of tourism. Today, visitors come in through the upper cave and exit via the lower entrance. Both caves contain paintings, but only the lower one has handprints.

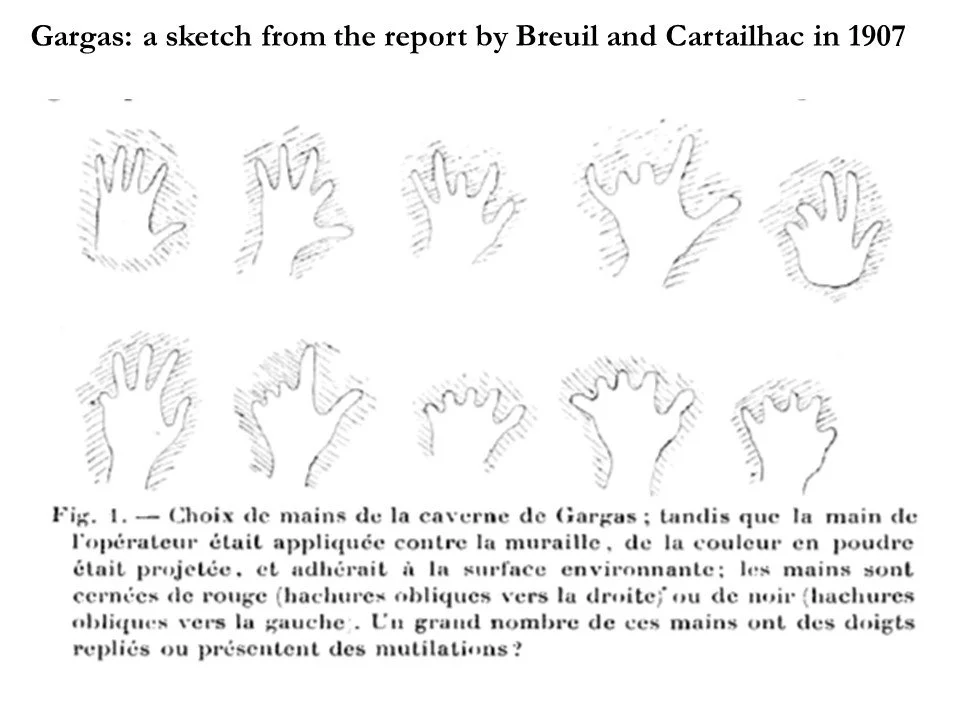

With a total of 231 handprints, the Grotte de Gargas contains 30% of all known handprints in Europe, and on a single wall near what is today the exit, archaeologists have counted 137, one yellow, the rest black or red. Inevitably, Breuil and Cartailhac were the first people to carry out a detailed inspection. In a report written after their second visit in 1907, they noted a peculiarity that has continued to generate hypotheses ever since: many of these handprints are missing a couple of phalanges from a finger or two, or sometimes all the hand’s fingers were mutilated in this way.

As with all works of prehistoric cave art, other mysteries include who produced them and why. The second of these questions is still in search of a plausible and generally accepted answer. As for the first, research in the last decade has come up with some curious findings.

The crucial difference between a handprint and, say, a painting of a bison is that one can deduce the gender and age of the artist. For example, modern men tend to have longer ring fingers than index fingers, while the opposite is true for women. This variation was more pronounced among our prehistoric ancestors, and a ten year research programme of handprints around the world concluded that around three-quarters of them belonged to females. And then in 2022, a Spanish study found that most of the artists had held their hands a short distance away from the wall, a technique that creates a slightly three-dimensional effect and enlarges the hand. As a result, they concluded that around a quarter were produced by children between the ages of two and twelve.

Talking of children, Gargas divides its visitors into groups of 25 and I was tagged onto the second half a busload of eight-year-olds. I have never before seen children so captivated by works of art.

FOLLOW THESE LINKS TO READ OTHER SECTIONS OF THIS POST:

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 1: Grotte d’Aurignac

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 2: Grotte de Niaux

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 3: Grotte de Bédeilhac

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 5: Grotte de Mas d’Azil

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 6: Caune de l’Arago and the Tautavel museum of prehistory