Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 3 - Grotte de Bédeilhac

Occitanie has played a central role in our understanding of prehistory, and Ariège boasts more prehistoric caves than any other department in France. Over a period of several months last year, I visited several of the ones that are open to the public. The prehistorians who were involved in the discovery or interpretation of these grottes were in many cases the same internationally renowned experts who explored even more famous caves which lie just outside my region (Lascaux, Les Eyzies and the Grotte de Chauvet, for example). They included people like Émile Cartailhac who, in 1882, took up a post at the faculty of science in Toulouse and became the first academic in France to teach prehistoric archaeology. And a young priest called Henri Breuil who, over the next 60 years, would become even more influential than Cartailhac. And more recently, Jean Clottes, the man who was called upon to assess the Grotte de Chauvet when it was rediscovered in 1994.

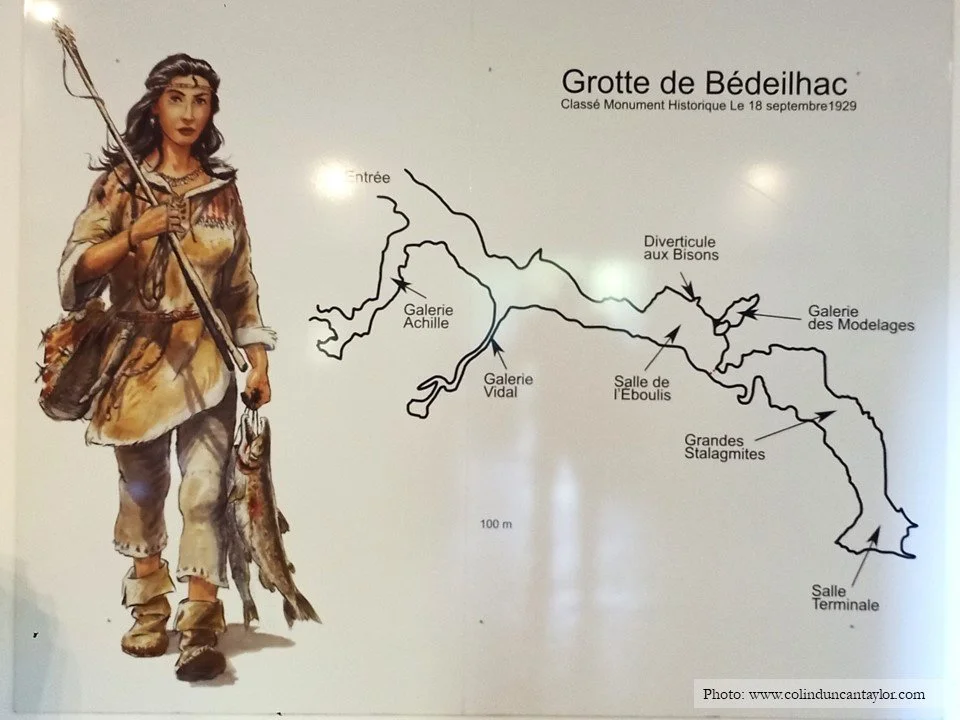

Grotte de Bédeilhac

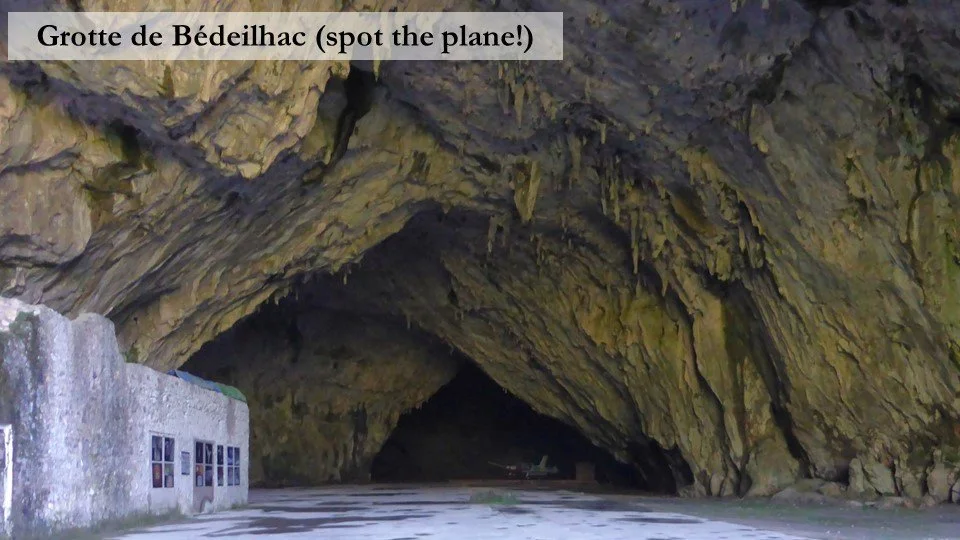

The Grotte de Bédeilhac is a few kilometres north-west of Tarascon-sur-Ariège. At first sight, it does little to evoke thoughts of prehistory. A wide concrete floor leads through the cavernous entrance and melts away into darkness. In the half-light, a small aircraft offers a misleading clue to the origins of this unusual surface.

In 1939, Emile Dewoitine planned to shift production of his D520 fighter plane from Toulouse to the Grotte de Bédeilhac where he would be safe from aerial bombardment. He even began some preparatory works, but France surrendered before his plans came to fruition. Then, soon after they took over Vichy France in November 1942, the Germans dug out the first few hundred metres of cave floor, levelled it with concrete and set up an underground workshop where they repaired Junkers 88s.

The presence of the light aircraft inside the entrance has helped created the myth that German bombers flew in and out of the cave. The true reason for its presence? In 1972, a test pilot called Georges Bonnet became the first pilot in the world to land in and take off from a cave. Two years later, Bonnet repeated his feat for a film, this time with his aircraft painted in the colours of the Luftwaffe. The plane on display today is the same model, but it was assembled on site using spare parts in 2010.

As for the prehistoric importance of Bédeilhac, its paintings of bison, horses, reindeer and ibex were first discovered in 1906 and subsequently verified by Breuil and Cartailhac. Abbé Breuil oversaw several other seasons of excavation, including one in 1941 shortly before the Germans bulldozed away so much of the floor and possibly destroyed other prehistoric artifacts.

Among the more unusual archaeological evidence are decorated objects and signs of toolmaking found 400 metres inside the Grotte de Bédeilhac. This is rare because early humans did not usually live or work deep inside caves. Apart from art, nearly all other signs of human activity have been found in or around cave entrances which offered a combination of shelter and natural light.

For me, the highlight of the visit was the presence of two positive handprints. They are called ‘positive’ because they were made by coating the hand with pigment before placing it on a surface, in this case a stalagmite. Examples of positive handprints are rare. Around 90 percent are negative, meaning that the person making them placed his or her hand against a wall and blew dried powder or pigment mixed with water through a hollow bone or reed, or even directly from the mouth, to create a stencilled outline. If you want to see negative handprints, the best place in the world is the Grotte de Gargas.

FOLLOW THESE LINKS TO READ OTHER SECTIONS OF THIS POST:

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 1: Grotte d’Aurignac

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 2: Grotte de Niaux

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 4: Grotte de Gargas

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 5: Grotte de Mas d’Azil

Prehistoric caves of Occitanie 6: Caune de l’Arago and the Tautavel museum of prehistory