Bison: the dominant theme in Pyrenean cave art

Visit some of the caves covered in my previous set of posts about prehistoric sites in Occitanie, and you will discover that the bison is the dominant theme in Pyrenean cave art. Curiously, the animals that were hunted the most often were not the same as the ones most frequently painted.

At the end of my visit to Mas d’Azil, I decided to head 50 kilometres east to La Ferme aux Bisons in the hope that a face-to-face encounter with a living, breathing bison might help me to understand why this beast inspired so many prehistoric artists.

On safari at the bison farm

At the farm, I soon forget what continent I am on. Our safari bus is a rickety trailer pulled along in bottom gear by a Massey-Ferguson tractor. We crawl past African Watusi cattle, their heads weighed down by horns a metre long, and a herd of Père David’s deer from China which eye us nervously from a shrinking waterhole.

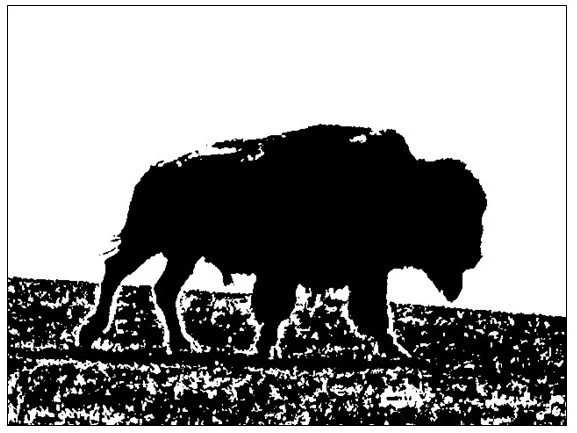

We rattle over a cattle grid and grind our way through a section of sparse oak woodland. The trees stop abruptly and the Pyrenees shimmer in the distance. Something catches my eye to the left, three silhouettes in a line where emerald green grass meets faultless blue sky. There is no mistaking the identity of this beast. The line of its back rises towards bulging shoulders and a massive horned head. For an instant, I forget the sunshine and think of the dark caves where I have seen this exact profile drawn or etched on the walls.

Hunted for half-a-million years

We inch our way forward and more bison come into view. In the wild, the sight of a human would send them galloping away into the distance, un understandable reaction when you remember that Tautavel Man was hunting them half-a-million years ago, and that our more recent ancestors drove them to the verge of extinction in both Europe and North America during the 20th century.

Humans have long been the bison’s principal predator, but the bison was rarely man’s principal prehistoric prey. Through all the different strata of the Caune de l’Arago, bison bones represent at most 10% of prey animals. They are far outnumbered by – depending on the strata – horse, deer, muskox, reindeer or wild sheep.

Tough characters

Based on observations of wild bison in North America where they face predators such as grizzly bears and wolves, we know that these animals stand firm in a group and face their enemy, horns at the ready. But should they choose to run, the bison is as fast as a horse and it can maintain a top speed of around 60 kilometres per hour for much longer than an equine. Despite weighing up to a tonne, it can do a standing jump higher than my head, pirouette on the spot and swim across raging torrents.

Seen in the wintry landscapes of the last Ice Age with their hot breath steaming in the bitter air, they must have inspired a mixture of fear and esteem, or even veneration, emotions which were subsequently expressed on the walls of many a prehistoric cave.

La Ferme aux Bisons

La Ferme aux Bisons lies slightly north of a line between Pamiers and Mirepoix. Please note that it is not a zoo. Founded in the 1990s to raise deer and bison for meat, it wasn’t profitable, so the owner decided to open his gates to the public. Meat production is now a sideline, but in the farm’s restaurant visitors still have the opportunity of tasting the meat of an animal that was hunted by the first humans who lived in the Pyrenees. It would, of course, be more representative of the Stone Age diet to choose venison which is also on the menu.