South of France, the Pyrenees and northern Spain

(latest to oldest articles)

The fairytale town of Alquézar

THE FAIRYTALE TOWN OF ALQUÉZAR / The very name of this quaint little town sounds Moorish, and indeed, Alquézar is thought to derive from the Arabic word for fortress. Around 1067, Alquézar was captured by the king of Aragon and a medieval Christian town developed. Today, it is listed as one of the most beautiful villages in Spain.

Where to discover prehistoric cave art in the Spanish Pyrenees…

ROCK ART IN THE SPANISH PYRENEES / The Sierra de Guara is the best place to discover prehistoric cave art in the Spanish Pyrenees. It also offers some of the best canyoning, rock climbing, hiking and trail running.

The extraordinary field system of Montady

THE EXTRAORDINARY FIELD SYSTEM OF MONTADY / The spoked-wheel fields of Montady are the result of a 13th-century project to transform a disease-ridden swamp into productive farmland: 400 hectares divided into 80 slices by 120 kilometres of drainage ditches.

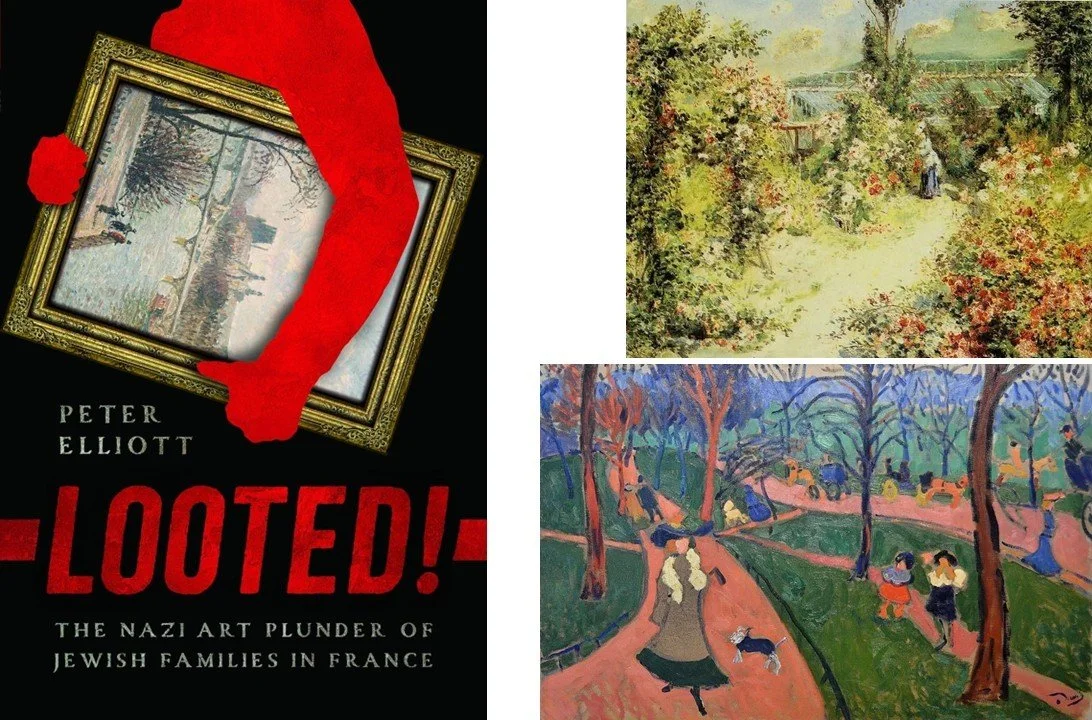

Book review: ‘Looted!’ by Peter Elliott

REVIEW OF ‘LOOTED! THE NAZI ART PLUNDER OF JEWISH FAMILIES IN FRANCE’ BY PETER ELLIOTT / ‘Looted!’ traces the rags-to-riches story of four French Jewish families and recounts the development of their interest in art collecting. It then explores how they fared during the Occupation, and how some of their artworks were looted by the Nazis while others were successfully hidden.

Marianne, symbol of the French republic

Marianne was not a real person. Like Eleanor Rigby or Maggie May, she was dreamt up for a song. Today in France, you will find her image on coins, postage stamps and government documents, and her bust is in most official buildings.

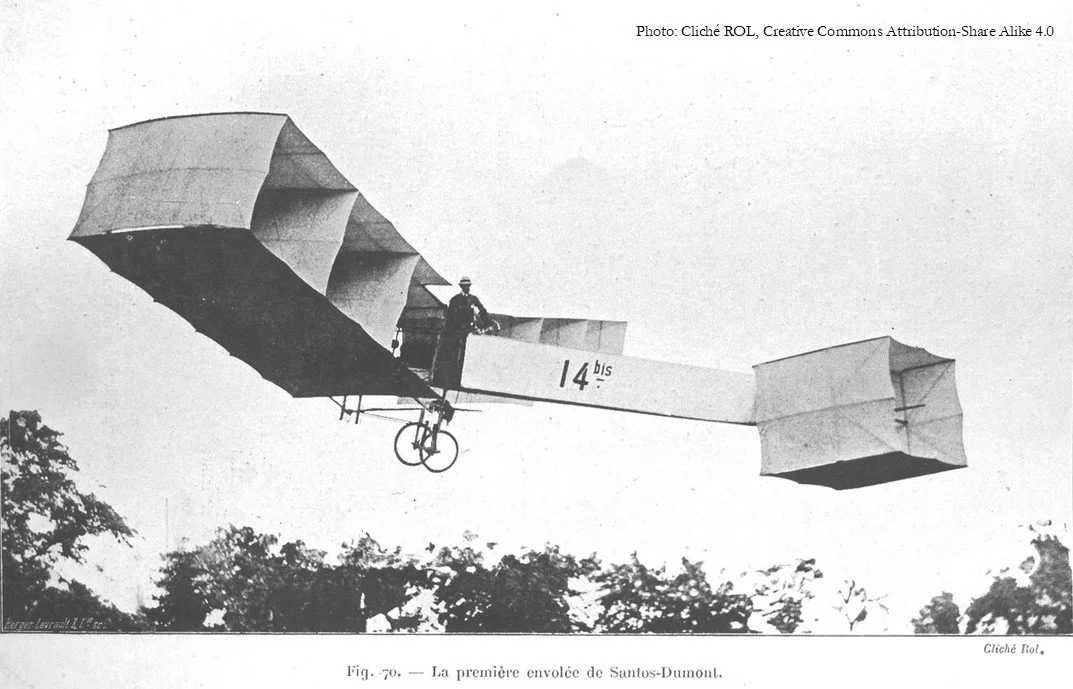

Astonishing tales from the earliest days of French aviation

In 1910, Armand Viguier built a pedal-powered aeroplane in his village church. When war broke out in 1914, he served successively as cavalryman, bomber pilot and fighter pilot. Learn more about his extraordinary career.

Toulouse: in memory of the exploding fertiliser factory

At 10.17 on 21 September 2001, Toulouse was shaken by an explosion which killed 31 people. The cause? A fertiliser factory run by AZF.

July 1381: The Battle of Montégut-Lauragais (or the Battle of Revel)

During the Hundred Years’ War, English and French armies clashed frequently on the battlefield. At the Battle of Montégut-Lauragais in 1381, a French count confronted a French duke.

The oldest café in Paris and the story of ice cream

Discover how ice cream helped a young Italian establish a cafe in 1686 that was frequented by Voltaire, Rousseau, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Danton and Robespierre.

Proud to be writing for Yale University Press

Please be indulgent and allow me to share a wonderful piece of publishing news! It's another good reason for me to love the Pyrenees.

The Resistance, the Bolivian and some deadly caterpillars

In a forest clearing halfway up a mountain, five granite figures stare into the distance and dream of freedom. Who carved them, and what do they represent?

A dramatic tomb for a forgotten playwright

With a poet’s eye for drama, Henry Bataille knew exactly how he wanted to be buried. Although his dramatic output has passed into oblivion, his tomb is unforgettable. It may even give you nightmares.

From brigand to metal-basher: explore the copper industry of Durfort

At the foot of the Montagne Noire, the village of Durfort devoted itself to copper for six centuries. Today, one or two shops still offer traditional wares, a copper vessel hangs outside nearly every house, and the village council has recently signposted a 3.5km walk along the river where trip hammers once thumped lumps of copper into shape.

Burnt offerings provide a rare insight into the medieval diet

Analysis of culinary remains – burnt and unburnt – that were discovered in a mountain village in the Montagne Noire provides a fascinating insight into what people were eating seven or eight centuries ago.

‘Give us this day our daily bread’: how grain silos improved food security in ancient times

The sixth line from the Lord’s Prayer asks God to provide us with the essentials that keep body and soul together. Long before those words were written, our distant ancestors took more practical steps to reduce the risk of dying of starvation in troubled times. A key part of their survival strategy was the silo.