A field of pastel During my extensive research into this ancient blue dye, the only people who have been able to show me a field of pastel grown in Occitanie are Bruno and Régine Berthoumieux. Over the years, I have made numerous visits to their family estate at the Château de La Serre near Cambounet-sur-le-Sor. I have trampled on their crop, watched the harvest, witnessed the transformation of green leaves into blue dye, admired the process of dyeing and even dipped the odd cloth into the vat myself. Recently, I was back there again, tagging onto a group of 30 Belgians who had come to learn more about the history of pastel and try a spot of dyeing for themselves. As a seasoned visitor, my eye was caught by something new – an exceptionally striking tee-shirt. Dyeing for charity In May this year, an association called ‘1000 étoiles pour l'enfance’ (1,000 stars for childhood) asked Bruno and Régine to transform some of their promotional tee-shirts by dyeing them with pastel. You can judge for yourself the success of this transformation thanks to these two photos taken by Régine. You may also like to decide if I’m too sexy for my shirt (too sexy for my shirt). If you can tear your eyes away from the tee-shirt, you will notice that the door beside me is also painted blue. People used to believe that this colour repelled insects. Modern science has discovered that paint made using pastel does indeed provide a natural protection against insects and some types of fungus, but the active ingredient is a transparent substance rather than the colour blue itself. ‘1000 étoiles pour l'enfance’ was founded in 2003 by an artist from the Tarn called Casimir Ferrer and it raises money to help ill children through activities including the sale of these tee-shirts. The design shows the Tour de France against a backdrop of Albi cathedral, inspired by the tour’s frequent visits to the town, most recently in 2019. To find out more about the Château de La Serre where you can experience pastel for yourself and even buy your own tee-shirt, visit www.pasteldelaserre.fr

0 Comments

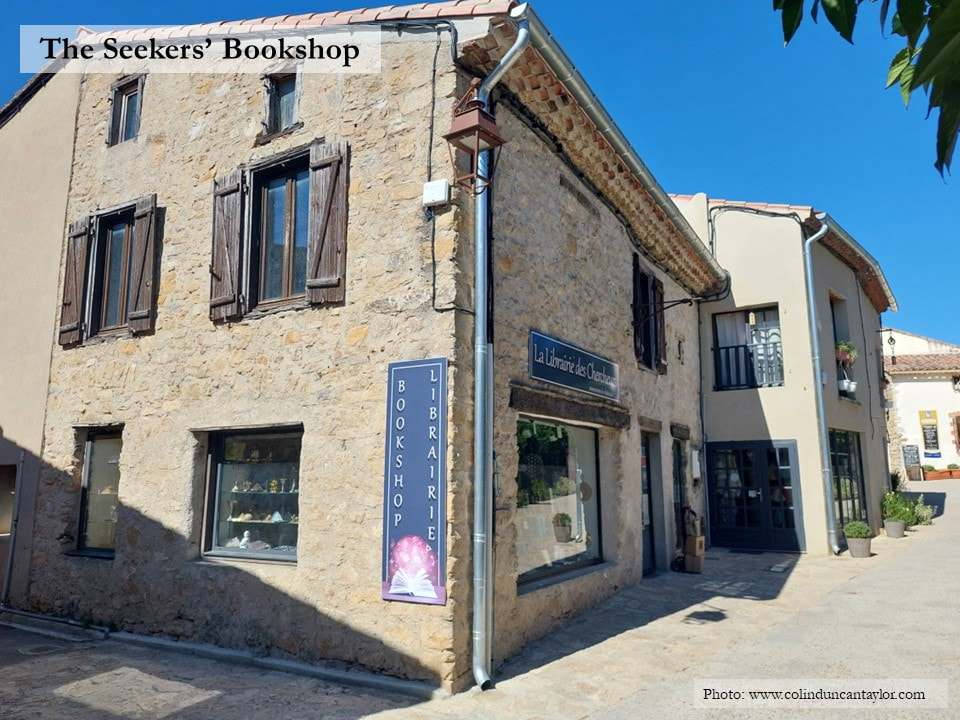

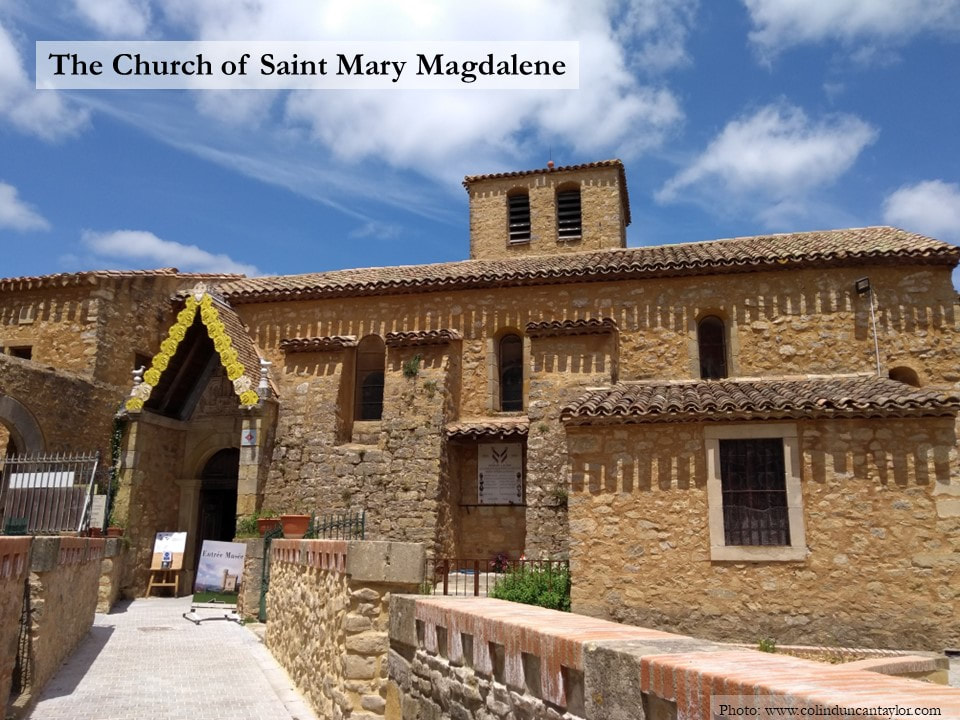

La Librairie des Chercheurs is not your average French bookshop. Nearly all the titles on its shelves address the same subject, and many of them are in English. If I tell you where The Seekers’ Bookshop is located, you may be able to guess what that subject is. Where did the money come from? Rennes-le-Château lies 30 kilometres south of Carcassonne. In 1887, its priest began restoring his church, presbytery and cemetery. A decade later, these works had cost Abbé Saunière the equivalent of €4.5 million in today’s money. Where had all this wealth come from, wondered his parishioners? One theory was that their priest had discovered some buried treasure. The bishop of Carcassonne thought otherwise, and in 1910 Abbé Saunière was called before an ecclesiastical court and charged with trafficking masses and indulgences. After a complex succession of legal wranglings during which Abbè Saunière failed to provide a satisfactory explanation for the source of his wealth, he was defrocked in 1915 and died two years later taking his secret to the grave. As well as financing the restoration works, Abbè Saunière had found enough money to buy various plots of land around the village, and to build himself a luxurious home (the Villa Béthanie) and a Neo Gothic tower which served as his library and place of meditation (the Tour Magdala). A genius of creative marketing After the second world war, his estate was acquired by a businessman from Perpignan. Noël Corbu turned it into a hotel-restaurant in 1955, but customers were rare because Rennes-le-Château was isolated on top of a steep hill which could only be reached by a perilous dirt road. A few months later, Monsieur Corbu had a simple but brilliant idea. Like everyone else in the village, he knew all the legends of fabulous treasure. All he had to do was reveal these stories to the outside world and curious visitors would flock to his establishment. He contacted Albert Salomon at La Dépêche du Midi, and in January 1956 three articles appeared under the series title ‘The fabulous discoveries of the billionaire priest of Rennes-le-Château.’ The final article was called, ‘Monsieur Noël Corbu knows the hiding place of the treasure of Abbè Saunière which is worth up to 50 billion [francs].’ If this claim had been true, Noël Corbu wouldn’t have been wasting his time running a hotel, and he certainly wouldn’t have revealed the whereabouts of his hoard. Nevertheless, within weeks his hotel and restaurant were full. Noël Corbu had other marketing tricks up his sleeve. In 1958, an article appeared in the local press claiming that Brigitte Bardot had been spotted incognito in the village. The photo was faked using a friend of Corbu’s daughter whose silhouette resembled the risqué actress. Less-famous but genuine French celebrities really did pay a visit, and Johnny Hallyday – France’s answer to Elvis – rang Corbu to book the whole place for him and his band when they were playing in Carcassonne. They were turned down because, despite the potential for publicity, Noël Corbu feared what a bunch of rowdy rockstars might do to his hotel.

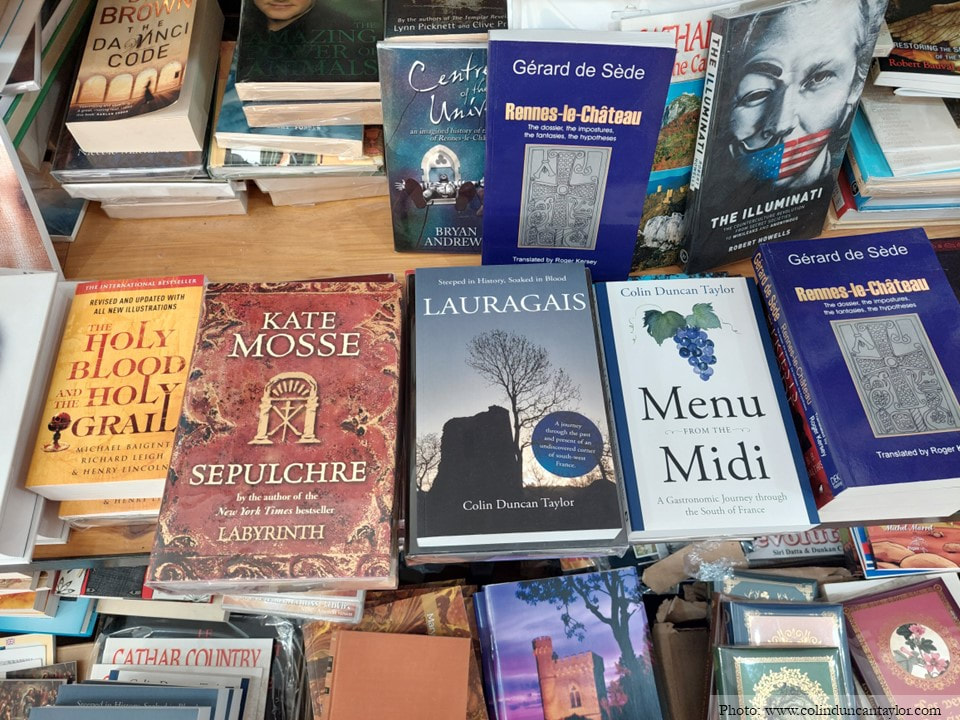

The stuff of legends and blockbusters All buried treasure has to be hidden by someone, so to whom had this mythical hoard first belonged? In the first press article, Corbu claimed it had been the property of Blanche de Castille, the 13th-century queen of Louis VIII. Over the next few decades, a succession of books – first in French then in English – embellished the story with other theories involving the likes of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, the Knights Templar, the Merovingian kings and the Cathars. The mystery of Rennes-le-Château was brought to the attention of the English-speaking world in 1982 when Henry Lincoln, Michael Baigent, and Richard Leigh wrote ‘The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail’. Since then, many other books including Dan Brown’s ‘The Da Vinci Code’ and Kate Mosse’s ‘Labyrinth’ trilogy have helped sustain the flow of visitors to Rennes-le-Château. I was there myself a couple of weeks of weeks ago because La Librairie des Chercheurs has agreed to stock my books. Never before have I found myself in such illustrious company, my two tomes rubbing shoulders with works by Henry Lincoln et al, Dan Brown and Kate Mosse. An unexpected stroke of luck Unlike Noël Corbu, my marketing coup was due to luck rather than a brainwave. A few weeks earlier, I had given a pre-dinner talk to an association. Several of its members had read and appreciated one or more of my books, and the president has known the owners of La Librairie des Chercheurs for 20 years. With her help, I was able to open the door to the bookshop and clear a space on its shelves. The name of this association? The Saunière Society, founded in 1985 to pursue the mystery of Rennes-le-Château. If you want to find out more about these mysteries, you might like to become a member of The Saunière Society, or browse the shelves of La Librairie des Chercheurs. If you want something less fanciful, try one of my books.

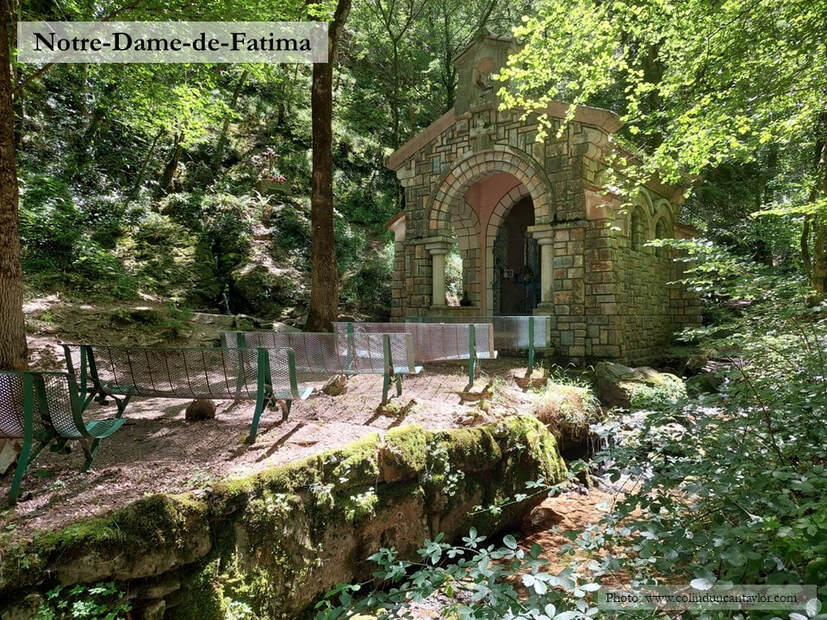

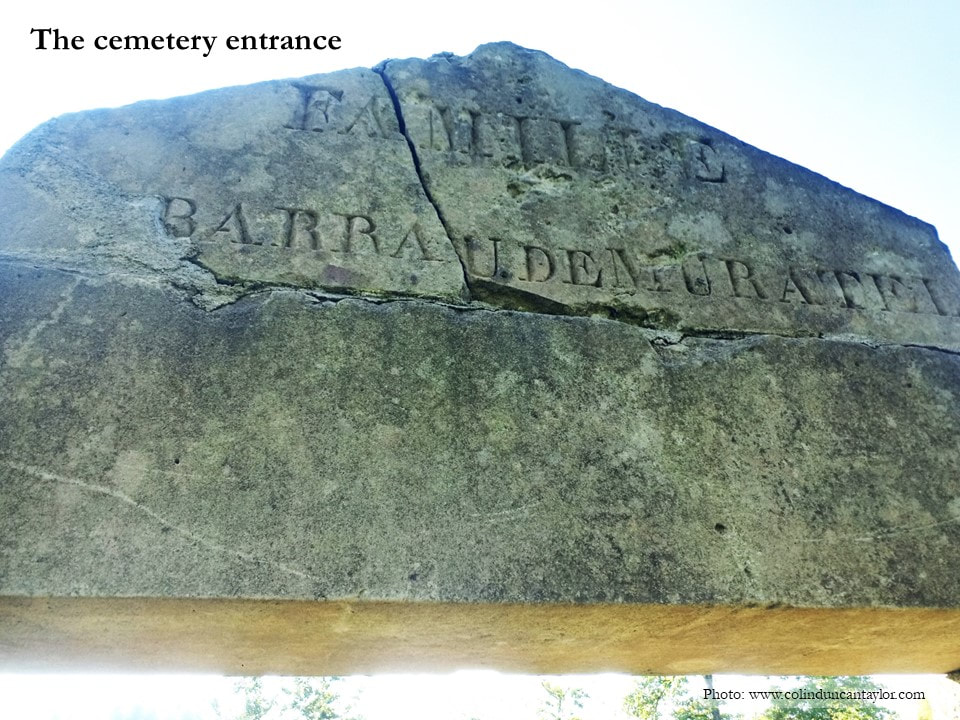

The glorious abbeys of the Montagne Noire justifiably attract crowds of visitors, but there are other pearls hidden up higher in the mountain. Here, I will reveal four of them, far beyond the reach of tour buses, places where solitude is almost guaranteed if you manage to find them. So read on and discover a secret Protestant cemetery, a long-abandoned church and a bijou monastery reclaimed by the forest. But first, I shall take you to a rustic chapel which would be the perfect location for hobbits and wood elves if they were organising a wedding. Hidden in the valley of the Baylou 2.5 kilometres south-west of Dourgne, this sylvan chapel has several names and legends. The current building was erected in the early 1950s to commemorate the homecoming of Dourgne’s youth after the second world war. Long before then, a hermit called Saint Macaire lived here besides the sacred fountain of Mouniès. Supposedly its water has magical properties, and the villagers used to come here to cure various afflictions by dabbing themselves with a cloth dipped in the spring. For the treatment to work, the cloth had to left behind in the forest. If you take a seat on one of the benches in the open-air nave and contemplate the chapel, soothed by the babbling brook and shaded by the forest, it is easy to understand why legends like this were born. Follow the valley upstream, and another magical place awaits you where the Melzic cascades down a rockface into a pool – perfect for bathing on a hot day. The Protestant cemetery of Grange Vielle Literally lost in the forest above Sorèze, you will need GPS coordinates to have any hope of finding this place, so here they are: 43°25'55.9"N 2°07'44.9"E or 43.432193, 2.129138. The cemetery is clearly visible on Google Maps satellite view, but that image is not recent and trees grow quickly! Long ago, the land in these parts belonged to the Benedictines, but during the Revolution it was bought by a Protestant nobleman called Cyr-Pierre de Barrau de Muratel. In the early 19th century, he built the Château de Grange Vieille on the north side of the road between Arfons and Sorèze, and created a family cemetery a few hundred metres away on the south side of the road. After the second world war, the Barrau de Muratels moved away and their cemetery was abandoned. In 2016, a team from Sorèze cleared the site and restored some of the graves. Photos taken at that time show a walled cemetery with tidy tombs, but the forest is not beaten so easily. My photos which accompany this text were taken in September 2021, and I fear by now the site may be even more overgrown. If you pay a visit, you may like to follow my example and pack a scythe or some secateurs. The Chapel of Saint-Jammes-de-Bezaucelle Just over a kilometre to the west of the Protestant cemetery lie the ruins of a chapel, founded in the 12th century (or perhaps even earlier) and abandoned during the Revolution when it was part of the estate bought by Cyr-Pierre de Barrau de Muratel. Its name and location suggest it may have had links with the Way of Saint James pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostella. More certainly, it served as the parish church for isolated farming communities such as Grange Vielle. Beside the chapel stands a majestic beech tree, 450 years old. In 2020, this was voted the most beautiful tree in France. The Chartreuse de La Loubatière In 2020, I tried my hand at archaeology and helped the Société d’Histoire de Revel Saint-Ferréol excavate a small monastery founded by the Bishop of Carcassonne in 1315 or 1320. The abbey’s church was about 25 metres long and 7 metres wide with walls at least a metre thick, and my job was to excavate the north-east corner from several centuries of soil, roots and rubble.

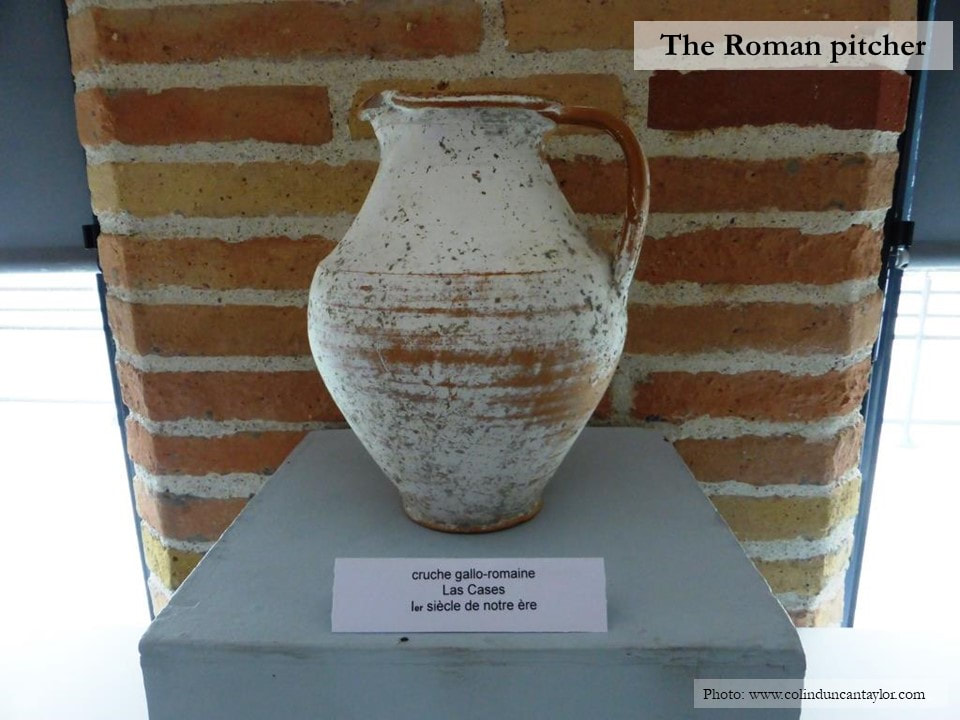

It was too tough for the monks to eke out a living up here in the mountains, 20 kilometres north of Carcassonne, and La Loubatière was abandoned after little more than a century. I found it so tough, I gave up my archaeological struggles after a single day. Luckily there were plenty of other volunteers to continue the good work. Most people visiting Las Cases barely glance at the château. Instead, they dive straight inside the farm shop to buy dried hams, sausages or fresh pork. The farm and château sit beside the main road from Revel to Castres, and before the Malinge family started making charcuterie, Las Cases had enjoyed a curious succession of occupants. From Stone Age to Romanisation The oldest objects discovered at Las Cases include flint arrow heads and polished stone axes from Neolithic times when humans were domesticating their first pigs. One day, Jean-Luc Malinge also discovered Roman relics while he was ploughing a field. He called in the archaeologists from Puylaurens, and more careful excavations unearthed a tilemaker’s workshop from the 1st century BCE. They also found pits where clay had been extracted and a building where the tiles were dried before being fired. The next year, Jean-Luc went looking for more remains and found an oven. Although it had been used by a tilemaker, he wasn’t a Gallo-Roman. Instead, the oven dated from the 13th century CE. People were making tiles at Las Cases for at least 1,400 years!

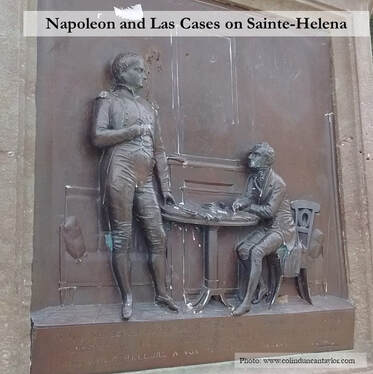

Remembering Napoleon We don’t know the names of the tilemakers, Roman or medieval. But in 1765, a young man was born in the Château de Las Cases whose name would be immortalised thanks to Napoleon.

The Memorial of Saint Helena In 1823, Las Cases published an eight-volume work in both French and English, drawing on his conversations with Napoleon. With Bonaparte dead, fear of the Corsican Ogre had already begun to turn to fascination, and thanks to its timely appearance, ‘Mémorial de Saint-Hélène’ became an international best-seller and remained popular into the 20th century. It also made Las Cases a very rich man. How much of ‘Mémorial de Saint-Hélène’ is truly based on Napoleon’s own words, and how much was imagined or embellished by the author, remains a matter of debate. Several people featured in the book were less than delighted with their portrayal, and Las Cases, fearing prosecution, made amendments or added further justifications in subsequent editions.

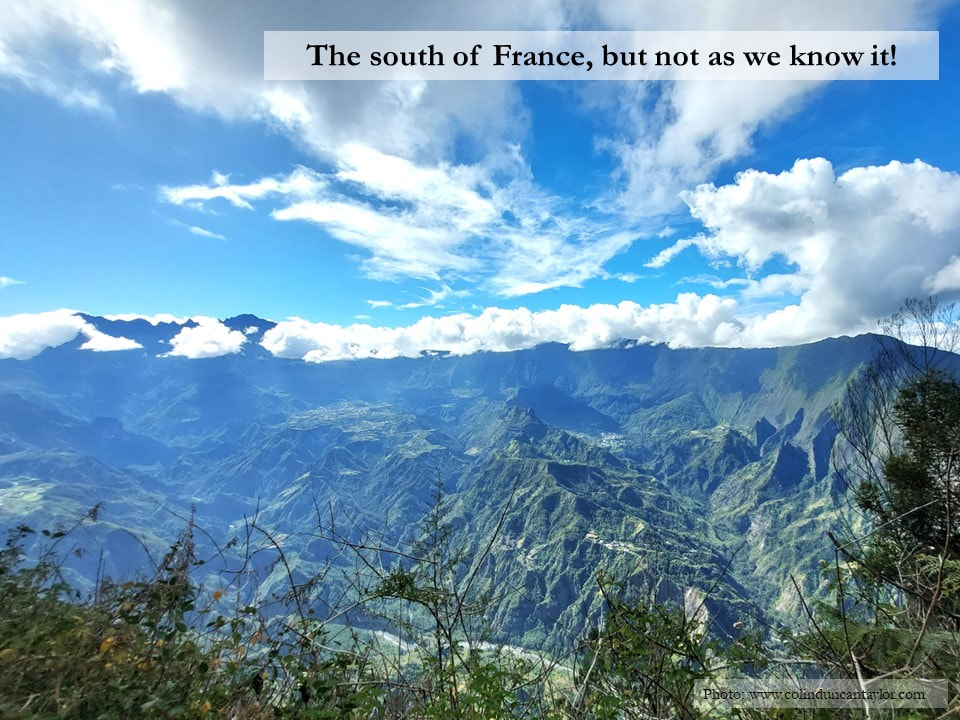

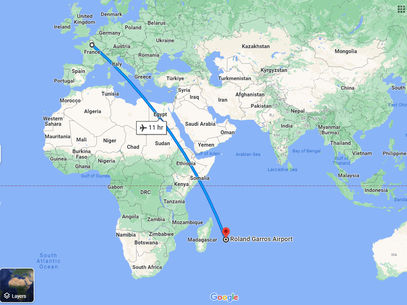

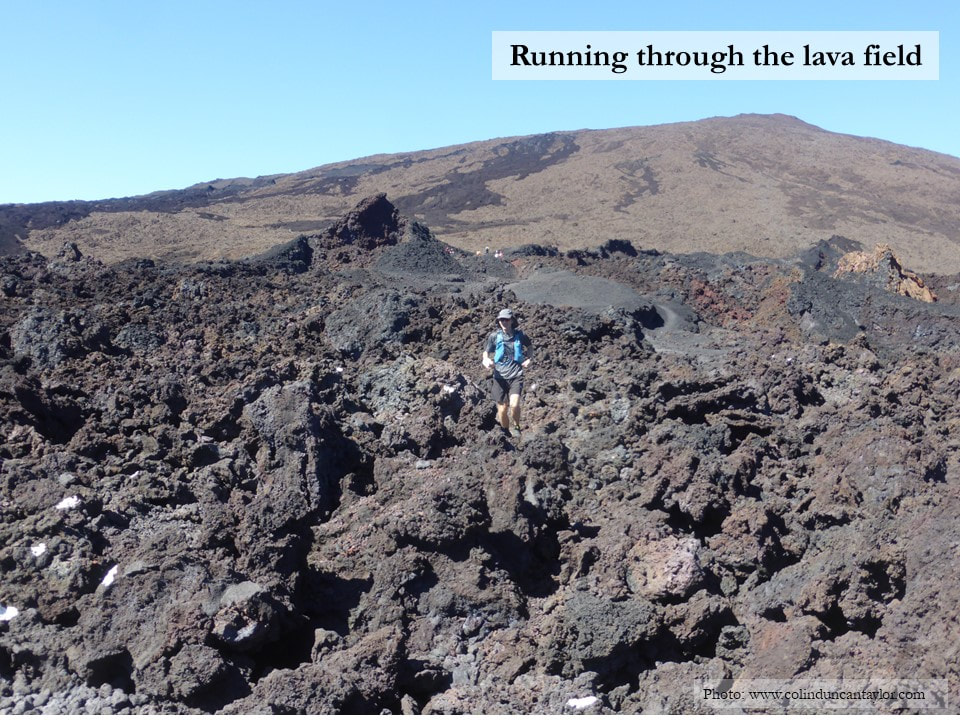

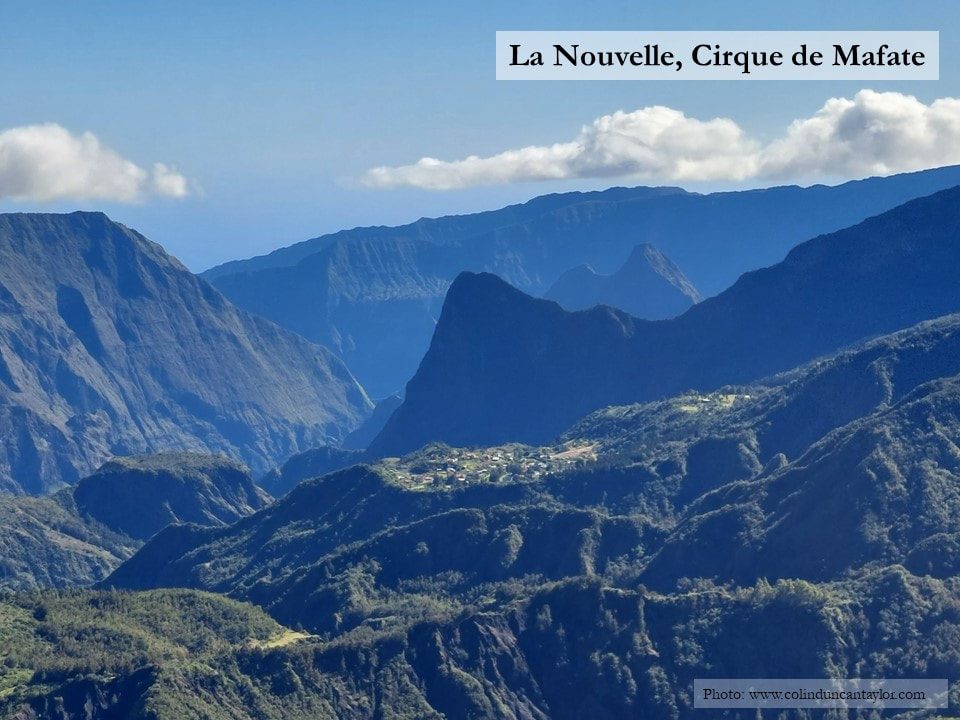

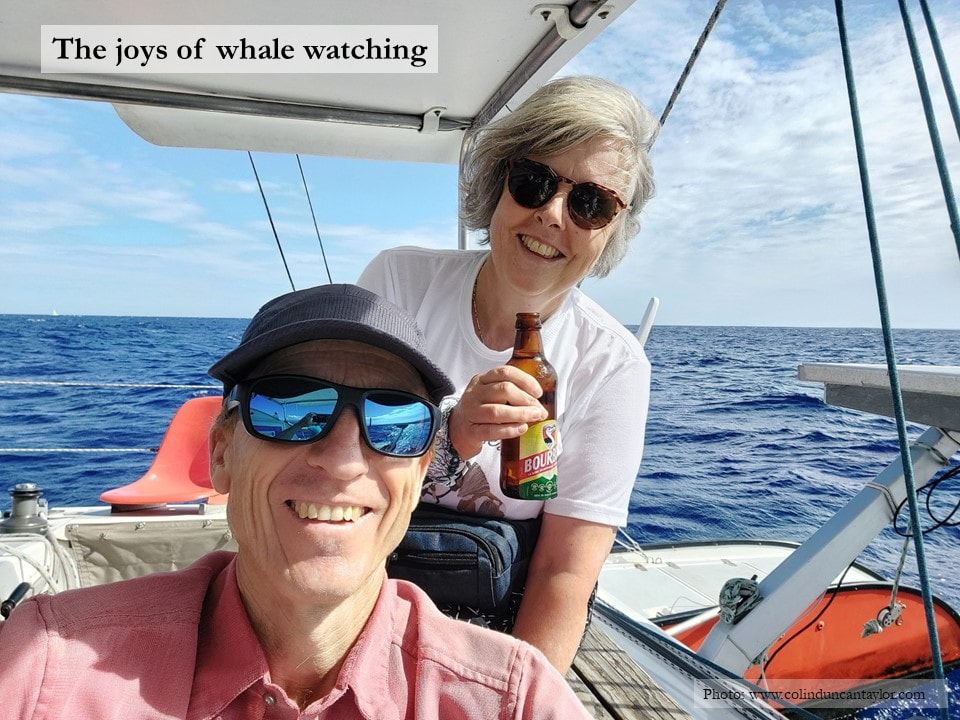

Given the name of this blog, I thought it was time to compose a few paragraphs about the most southerly of the 101 départements français. In the part of France that lies in mainland Europe, the most southerly department is Pyrénées-Orientales. Look a little more widely, and what is often referred to as France Metropolitaine includes Corsica, an island that is split into two departments with nearly all of Corse-du-Sud being south of the border between Pyrénées-Orientales and Spain. But there are five more departments overseas, and two of them lie south of the equator in the Indian Ocean on opposite sides of Madagascar. To visit the most southerly part of France, I took a 9,000-kilometre flight from Paris to the island of La Réunion. In administrative and legal terms, this is a true French department, and bizarrely this also makes La Réunion the most far-flung corner of the European Union. One of the most active volcanoes in the world La Réunion is a volcanic island. Its south-eastern end is dominated by the Piton de la Fournaise, one of the most active volcanoes in the world. Since the first colonists arrived in the mid-17th century, it has erupted over 200 times. When I climbed it on 14 June 2023, I was a little perturbed by the warning sign: AN ERUPTION IS PROBABLE IN THE NEXT FEW DAYS. BE CAREFUL. Fortunately for me, this latest eruption did not begin until I was safely back in France Metropolitaine. At 08.50 on the morning of 2 July 2023, lava began oozing out of the volcano’s southern slope. You can view photos and videos in the French press. A far more spectacular and unusual eruption took place in 2007. The summit of the volcano is 2,632 metres above sea level, but on this occasion magma spewed out of the eastern slope at an altitude of only 600 metres. Within a few hours, the lava had run all the way down the mountain and into the Indian Ocean. The road that runs around the island has since been rebuilt and runs through this barren volcanic landscape. Its name? Lava Road. Saved by a miracle A little further north, the eruption of 1977 left an even more striking sight thanks to what some regard as a miracle. When lava began to flow down the mountain, 1,500 inhabitants from the village of Piton Sainte-Rose were evacuated. Part of their village was destroyed, but when the lava reached the church, it flowed around both sides, destroyed the west door but stopped short of the nave. All the stained glass exploded due to the intense heat and the floor was damaged, but otherwise the church was spared. Subsequently it was renamed Notre Dame des Laves, and although this event may not have been a miracle, it certainly created an unforgettable sight. The highest mountain in the Indian Ocean Piton de la Fournaise is around 500,000 years old, but the original volcano that created the island of La Réunion emerged from the ocean around three million years ago. Known as Piton des Neiges, it grew through a series of eruptions. Today, at 3,070 metres above sea level, it is the highest mountain in the Indian Ocean. Piton des Neiges has been dormant for around 10,000 years, and during this time erosion has created three vast cirques: Cilaos, Mafate and Salazie. For the fit and active, these cirques provide a challenging and stunning environment for a range of outdoor adventures. I spent two days hiking into, around and out of Mafate, spending the night in a simple wooden hut in a tiny village called La Nouvelle. There are no roads in Mafate, but around 700 people live there, mainly surviving through tourism and subsistence farming. Pity the postman and the priest Most supplies are flown in by helicopter, which can make the morning skies surprisingly noisy, but spare a thought for the postman who has to deliver letters to these 700 inhabitants. La Poste is disinclined to give postie a helicopter so he has to carry 10-15 kilograms of mail on his back up and down some of the steepest slopes I have encountered. Luckily he only does one or two rounds a week. I was also intrigued to meet a priest standing outside the church preparing to celebrate mass. The Lord may give him wings, but not a helicopter, so he too is obliged to travel in and out by foot. I suspect this gentleman is the fittest priest I have ever met. No doubt he also gives a good mass, but after a long day in the mountains I was more tempted by researching the local beer. The right hand photo below also illustrates that, although during our stay the weather by the coast was usually dry, hot and sunny, late afternoon and evening in the mountains invariably brought mist, rain, a storm or all three. Whale watching Away from these wild and inaccessible areas, most visitors head for the west coast where the sand is golden instead of black and a reef protects swimmers from shark attacks. Between July and October, this is also an outstanding location for spotting humpback whales, and I had the good fortune to view one of this year’s early arrivals while he circled our catamaran. The changing face of a tropical island

Until the first colonists settled on the island in the mid-17th century, La Réunion was uninhabited. In the 18th and 19th centuries, coffee, spices and sugar cane dominated an economy which was largely dependent on imported slaves. When slavery was abolished in 1848, the population comprised 45,000 free men and 65,000 slaves. After three centuries as a colony, La Réunion became a French department in 1946. In 2020, the population reached 860,000, putting La Réunion in the top quarter of the most populated French departments. In terms of population density, it’s in the top dozen. With Piton de la Fournaise occupying around one third of the island’s entire surface, and much of the land around Piton des Neiges being too vertiginous to be habitable, most of the population is squeezed into a busy coastal strip. Nevertheless, there are few large hotels and tourism feels refreshingly low-key. Would I make another visit? Definitely!

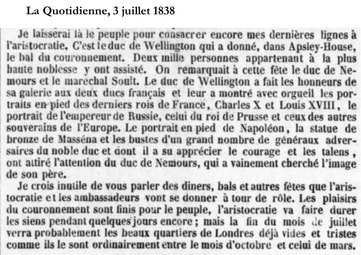

From political exile to founder of the Foreign Legion When Louis XVIII was restored to the throne, even Soult’s political skills couldn’t save him from exile. But after four years in Germany, he was allowed to return to France where Louis XVIII restored him to the rank of marshal. Charles X awarded him a peerage and Louis-Philippe made him minister of war. As part of his plans to expand the army, Soult created the Foreign Legion in 1831. By this time, he had also begun a construction project in his home town. His wife’s maiden name was Berg, and their new home became the Château de Soult-Berg. It was completed in 1835. Queen Victoria’s coronation In 1838, Louis-Philippe chose Soult to be his representative at the coronation of Queen Victoria in London. As far as I can determine, Soult and Wellington never met face-to-face during all the years they spent fighting each other in Portugal, Spain, France and Belgium. But according to the tale I was told during my visit to Soult-Berg, this long-overdue encounter took place at the time of the coronation. Supposedly, while Soult was at a banquet, Wellington crept up behind him, grabbed his shoulders and cried, ‘I’ve got him, by damme; I’ve found you at last, Marshal Soult!’ And the next day, the two men rode around London in a carriage admiring the sights and receiving rapturous applause. I had always doubted this story until I came across a piece in the 3 July 1838 edition of the French daily newspaper La Quotidienne, written by its London correspondent two days after the coronation.

Although there is no mention of the two former foes taking a carriage ride together, the idea of Soult receiving rapturous applause from the public is believable. According to Nicole Gotteri’s authoritative and monumental biography of Soult, this visit to London was among the highlights of Soult’s career, one of his most glorious campaigns. At the age of 69, a man who had spent so many years fighting the British was treated like a hero, received too many invitations to accept, visited the main sights in London, made trips to Windsor, Liverpool and Manchester, and hosted a ball in his ambassadorial residence where 1,000 high-society guests danced until five in the morning. The Château de Soult-Berg When Soult returned to France after this triumphal visit, Louis-Philippe appointed him foreign minister. Soon after, he added the role of prime minister, and at various times during the next seven years he also held the post of war minister. In 1847, Soult retired from politics and returned to his home at the Château de Soult-Berg. One of his first acts was to order the construction of a grand mausoleum attached to the parish church. On 26 November 1851 he died at home and was buried in this neo-classical tomb where the highlights of his career as a soldier and a politician are engraved in white marble. Shortly before the day of Soult's funeral, the town honoured its most famous son by changing its name to Saint-Amans-Soult. It lies ten kilometres east of Mazamet, in the department of the Tarn and in the shadow of the Montagne Noire. Note: all photographs of painted portraits were taken inside the Château de Soult-Berg.

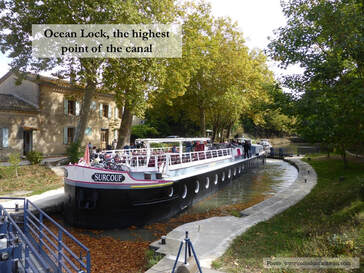

Naurouze is one of those places that seems to attract legends and history, as well as being notable from a geological and geographic perspective. It is located south-east of Toulouse, conveniently close to the main road between Villefranche-de-Lauragais and Castelnaudary.

Unfortunately, this event is a legend because it had long been known that Naurouze was a watershed. Riquet’s genius lay in working out how to collect and channel a large volume of water from the Montagne Noire to Naurouze.

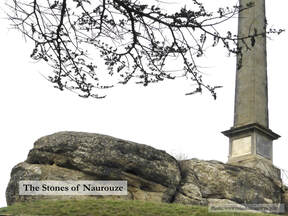

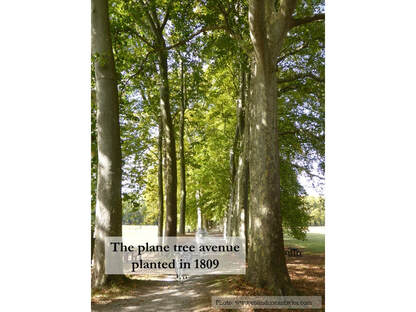

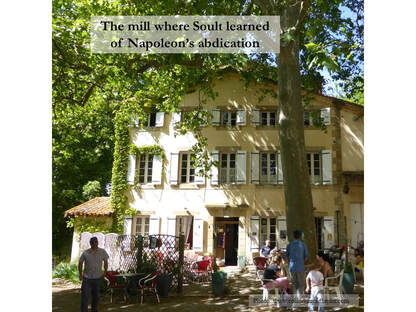

The monument to Pierre-Paul Riquet Even in a place so rich in legends, Riquet is quite literally a towering presence. In 1825, his family decided that the Stones of Naurouze would make a perfect pedestal for a monument to his memory. Unfortunately, they also decided to protect their obelisk by encircling the site with a stone wall nearly three metres high, with a single entrance which is firmly sealed by locked iron gates. A short stroll between the obelisk and the canal takes you down the Chemin des Légendes, past the engineer’s house and a flour mill built by Riquet and along a path lined with plane trees planted in 1809. This shady avenue traverses an octagonal island, 400 metres from side to side, encircled by a channel bringing water from the Montagne Noire to the canal. Originally, this island was a basin built by Riquet to store more water for his canal, but unfortunately it soon silted up and was abandoned to become a grassy meadow. Just beyond the island is the highest section of the canal. A legendary meeting between Wellington and Soult Another legend claims that after the Battle of Toulouse in 1814, Soult and Wellington met at Naurouze and signed their armistice. This too is untrue, although Marshal Soult did indeed stop at this mill on 13 April 1814, and it was here that he received Wellington’s aide-de-camp and a French officer who brought dispatches and newspapers from Paris telling him that Napoleon had abdicated. Roman remains

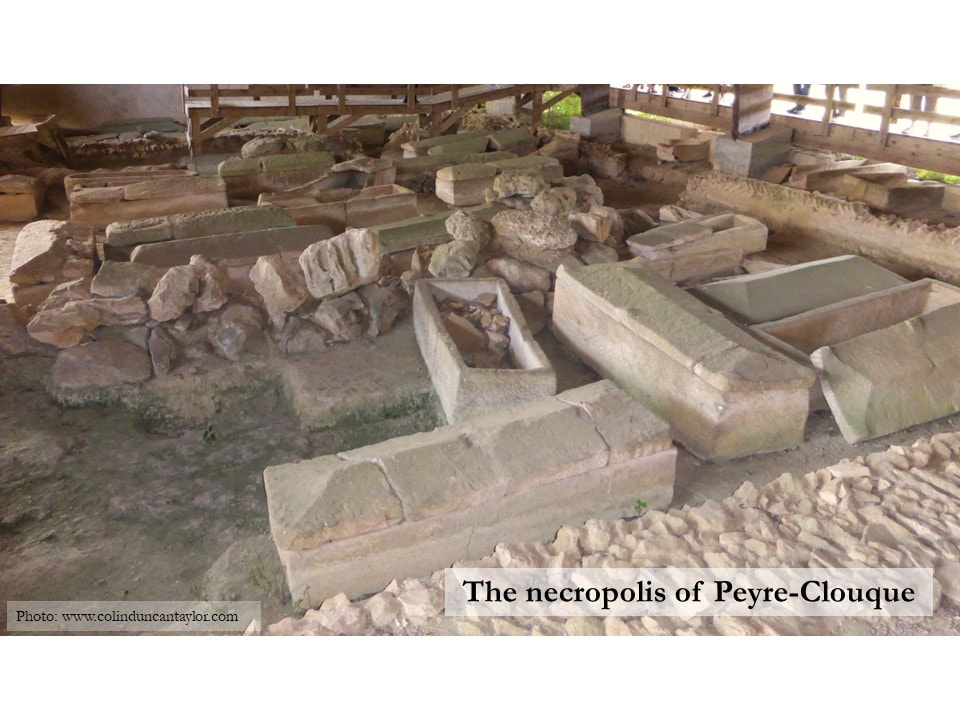

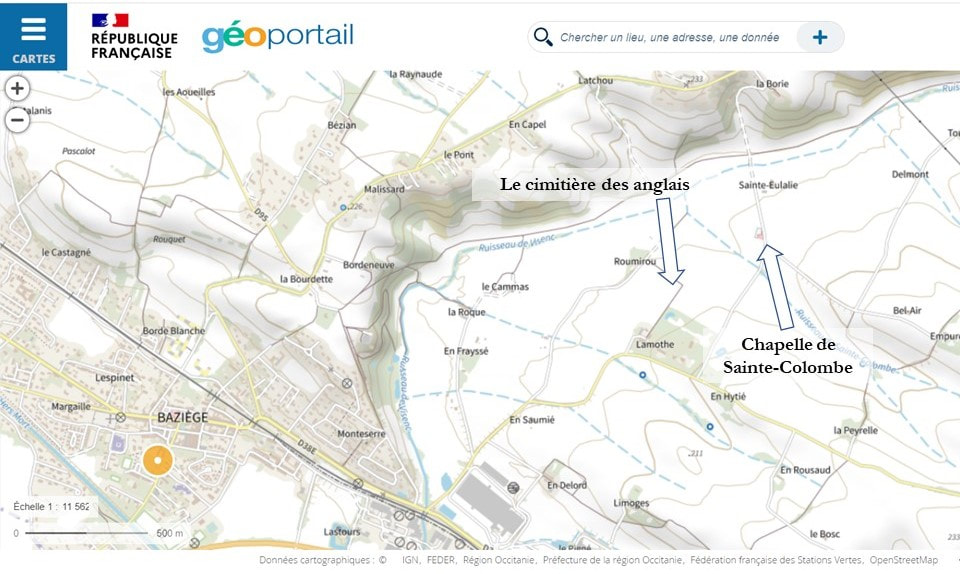

Even that does not exhaust the supply of stories at Naurouze. Two thousand years ago, the Via Aquitania passed through here a few paces to the north, and the Roman town of Elusio grew up alongside it. In the twelfth century, the church of Saint Pierre d'Alzonne was built on the Roman remains, and inside the church porch you can see a collection of unusual discoidal gravestones. Just beyond the church is another site, Peyre-Clouque, which includes the remains of Elusio’s Roman baths and a collection of 52 stone coffins dating from the 6th century CE. Note that Peyre-Clouque can only be visited by prior arrangement (contact the mairie in Montferrand for up-to-date details). Two places to the east of Toulouse are known as le cimitière des anglais, or the English cemetery. The question is, are any Englishmen buried there? This story follows on from my previous post about the Battle of Toulouse, fought on 10 April 1814 between the armies of Wellington and Soult. In that post, I explained that Wellington’s allied army included troops from all corners of the British Isles, several German cavalry regiments and a large number of Spanish and Portuguese units. The retreat along the Canal du Midi The day after the battle, Marshal Soult and his army retreated along the south bank of the Canal du Midi. The allies were scouting the hills to the north, so Soult’s engineers blew up the bridges along the canal to keep them at a safe distance. The French planned to cross the canal at Baziège and follow the old Roman road towards Castelnaudary. To protect this crossing point, Soult posted infantry and cavalry units in the hills above Baziège to stop the allies attacking the long column of his retreating army. The Battle of Baziège A detachment from the French 75th infantry regiment took up a position in the grounds of the Château de Lamothe, two kilometres north-east of Baziège. Four hundred metres to the north-east of the château stands the chapel of Sainte-Colombe, and inside its porch is a brief account of a cavalry clash that took place in the surrounding fields on 12 April 1814. At the end of it, 25 French and 52 allied cavalrymen lay dead.

The account in the chapel’s porch claims the allied dead came from the 5th dragoons, a British regiment. My own research suggests they came from a brigade that comprised an Anglo-Irish regiment (the 18th hussars) and the 1st hussars of the King’s German Legion. This cimitière des anglais is unlikely to be filled with Englishmen, although there may be few.

Le cimitière des anglais? Le cimitière des irlandais? Le cimitière des allemands? No one knows for sure.

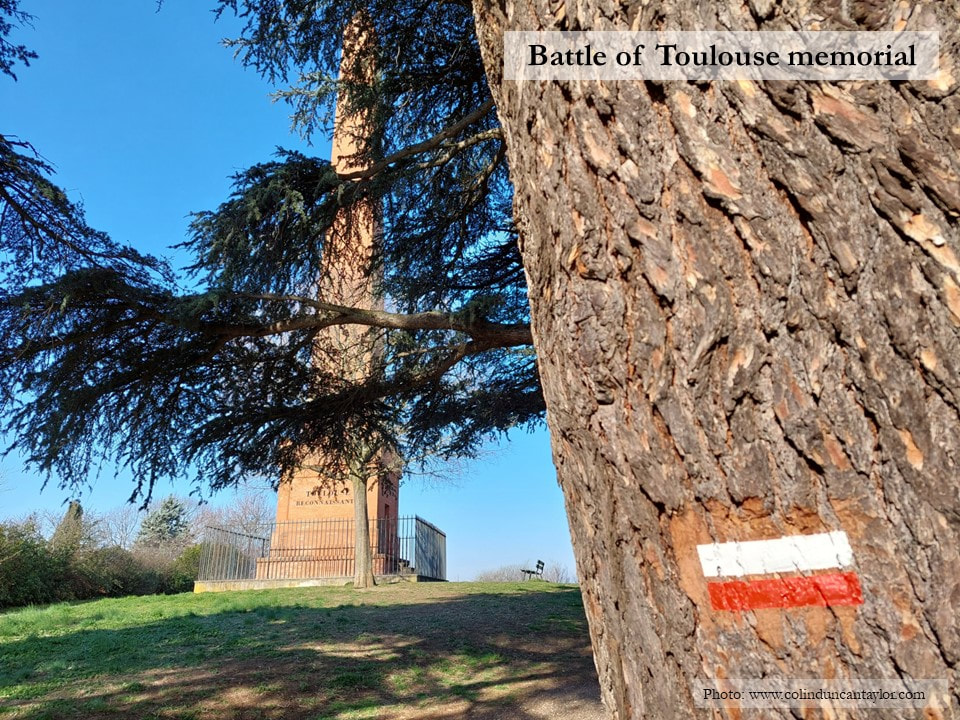

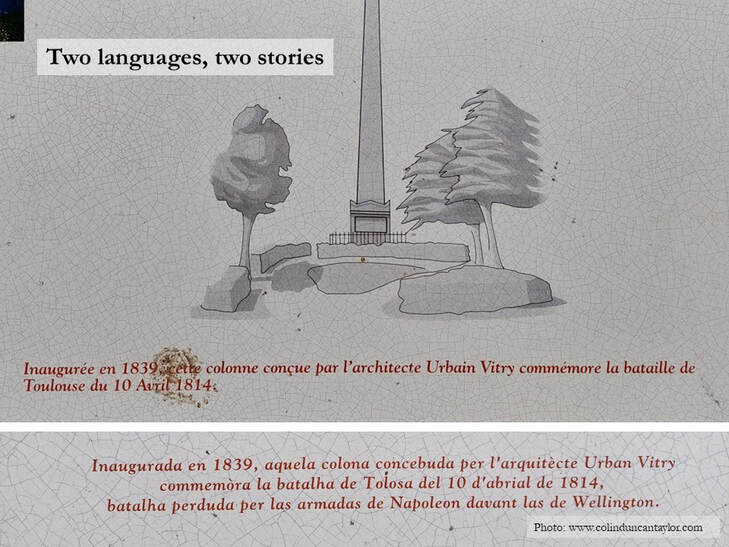

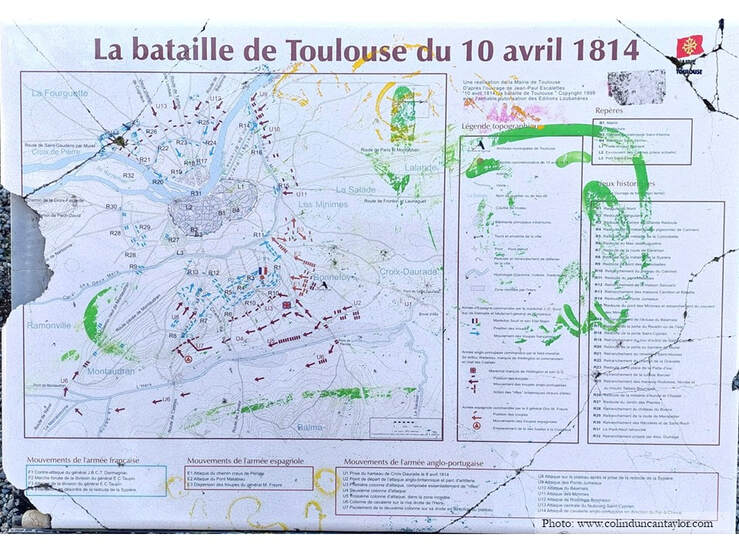

If you are walking the GR46 long-distance footpath, or simply enjoy exploring Toulouse beyond the Place du Capitole, you may encounter this imposing memorial column on a hill behind Matabiau railway station. Whenever I see it, the word ‘folly’ comes to mind, not with regards to the monument but because it commemorates a pointless and bloody battle in which 1,000 men lost their lives and over 6,000 were wounded. Spot the difference between French and Occitan There are two plaques beside the column, one in French, one in Occitan, and anyone who can understand both languages will notice an intriguing difference between the two texts. Both tell us that the column was inaugurated in 1839 and designed by the architect Urbain Vitry to commemorate the Battle of Toulouse, 10 April 1814. The Occitan version then adds an extra phrase: ‘a battle lost by the armies of Napoleon against those of Wellington.’ This reflects the fact that at the time the column was being built, some French officers were disputing their defeat. Toulouse, in contrast, had retained a strong royalist sentiment throughout the Napoleonic period, as Wellington discovered for himself after the battle. The fighting on 10 April lasted from dawn to dusk. A larger information board near the memorial shows how the battle unfolded, although anyone with that level of interest would be better advised to read Edouard Lapène’s, ‘Evènements Militaires devant Toulouse en 1814’ which can be viewed for free on Google Books, or my book ‘Lauragais: Steeped in History, Soaked in Blood’. A royalist welcome for Wellington The next day, Marshal Soult and his army slipped out of town along the Canal du Midi. On 12 April, Wellington and his troops entered the city to cries of ‘Vivent les anglais!’, ‘Vive Louis XVIII!’ and ‘Vivent les Bourbons!’ In the Place du Capitole the crowds tore down the bust of Napoleon and dragged it towards the river. Ladies distributed white royalist cockades from their baskets, and inside the Capitole building even the city officials wore the royalist symbol when they welcomed the allied commander-in-chief. Inside the Salle des Illustres, Wellington was visibly perturbed. He warned the assembled dignitaries that their royalist zeal was premature, and perhaps dangerous to their persons; he was still waiting for news from Paris, and a peace treaty with Napoleon remained a possibility; the return of the king was by no means certain. Late news or fake news? Within a few hours, Wellington learned the truth: he had fought an unnecessary battle. Two colonels – one English and one French – brought him dispatches and newspapers from Paris: Napoleon had abdicated unconditionally on 6 April, Louis XVIII had been declared king, and the provisional government had ordered all the armies of France to suspend hostilities. The messengers had left Paris on 7 April, but they reached Toulouse too late to prevent the battle. It took another week to convince Marshal Soult that the news from Paris was genuine, a long week during which several bloody skirmishes took place in the fields of the Lauragais. On 19 and 20 April, copies of an armistice were shuttled back and forth along the Canal du Midi between Toulouse and Narbonne for signature by Wellington, Soult, and Marshal Suchet who commanded the French army in Catalonia. Both sides claim victory When the Napoleonic Wars were finally over, some French officers began to question who had really won the Battle of Toulouse. This dispute reached its height in 1837 when a French military engineer, Pierre-Marie Théodore Choumara, wrote a book in which he argued that because the allies lost more men, and because Soult remained in control of Toulouse and merely lost some defensive positions outside the city before choosing to withdraw, the French army was victorious. When Wellington was shown the book, he predictably wrote a long and indignant rebuttal. Given that the battle had served no purpose, it is reasonable to wonder why anyone cared. The explanation lies, perhaps, in the broader historical context. Ever since the Norman Conquest of 1066, the kingdoms of England and France had usually been at war, and occasionally in a state of uneasy peace. The 26 years between the start of the French Revolution and the downfall of Napoleon was one of the most intense periods of this long conflict.

On safari at the bison farm At the farm, I soon forget what continent I am on. Our safari bus is a rickety trailer pulled along in bottom gear by a Massey-Ferguson tractor. We crawl past African Watusi cattle, their heads weighed down by horns a metre long, and a herd of Père David’s deer from China which eye us nervously from a shrinking waterhole. We rattle over a cattle grid and grind our way through a section of sparse oak woodland. The trees stop abruptly and the Pyrenees shimmer in the distance. Something catches my eye to the left, three silhouettes in a line where emerald green grass meets faultless blue sky. There is no mistaking the identity of this beast. The line of its back rises towards bulging shoulders and a massive horned head. For an instant, I forget the sunshine and think of the dark caves where I have seen this exact profile drawn or etched on the walls. Hunted for half-a-million years We inch our way forward and more bison come into view. In the wild, the sight of a human would send them galloping away into the distance, un understandable reaction when you remember that Tautavel Man was hunting them half-a-million years ago, and that our more recent ancestors drove them to the verge of extinction in both Europe and North America during the 20th century. Humans have long been the bison’s principal predator, but the bison was rarely man’s principal prehistoric prey. Through all the different strata of the Caune de l’Arago, bison bones represent at most 10% of prey animals. They are far outnumbered by – depending on the strata – horse, deer, muskox, reindeer or wild sheep. Tough characters Based on observations of wild bison in North America where they face predators such as grizzly bears and wolves, we know that these animals stand firm in a group and face their enemy, horns at the ready. But should they choose to run, the bison is as fast as a horse and it can maintain a top speed of around 60 kilometres per hour for much longer than an equine. Despite weighing up to a tonne, it can do a standing jump higher than my head, pirouette on the spot and swim across raging torrents. Seen in the wintry landscapes of the last Ice Age with their hot breath steaming in the bitter air, they must have inspired a mixture of fear and esteem, or even veneration, emotions which were subsequently expressed on the walls of many a prehistoric cave.

|

Colin Duncan Taylor"I have been living in the south of France for 20 years, and through my books and my blog, I endeavour to share my love for the history and gastronomy of Occitanie and the Pyrenees." |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed