The Pyrenees: A Human History

‘The Pyrenees: A Human History’ will be published by Yale University Press in London on 25 August 2026, and in New Haven, Connecticut on 8 September 2026. The book is available for pre-order now.

The Pyrenees dominate the landscape between France and Spain, stretching from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean. Long thought of as an impassable, unspoiled wilderness, the mountains are often seen as both a physical and cultural barrier between southern Europe and the Iberian Peninsula. Yet this treacherous terrain has been inhabited and shaped by human hands for millennia.

This book guides us through the human history of the Pyrenees, from the cave art of their first prehistoric inhabitants to today’s spa towns and ski resorts. Early pastoralists, Greek and Roman colonists, the Visigoths and the Moors all left their mark on the mountains, and the Pyrenees have played an outsize role in European history — as a place to live or hide, attack or defend, exploit or enjoy.

The author collects together stories from both sides of the mountains and reveals how they have been made and remade throughout history by people from all levels of society.

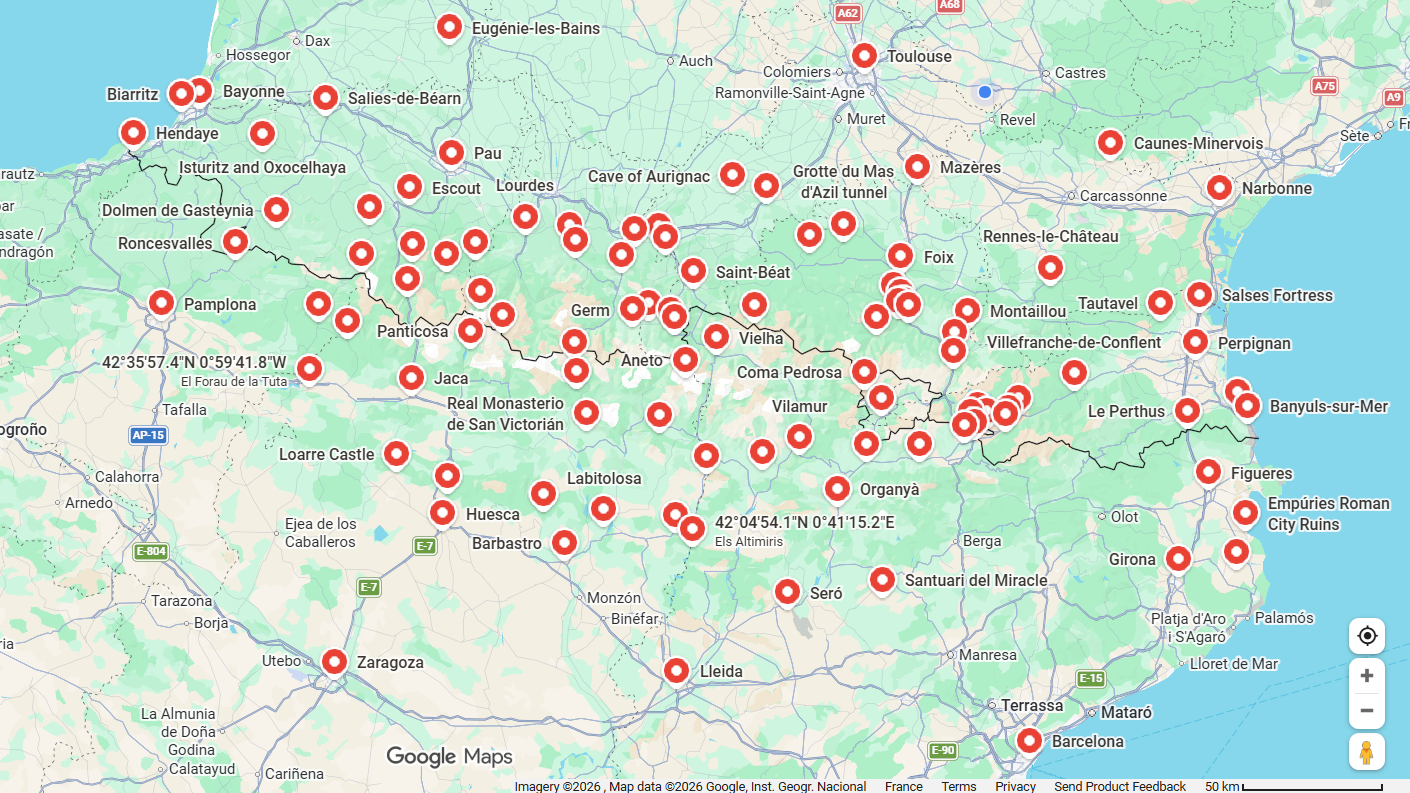

Map showing many of the places explored in the book 'The Pyrenees A Human History'.

Subterranean Secrets

An eclectic mix of people have left behind mysterious reminders of their underground activities in Pyrenean caves. These include the owner of the oldest face discovered in Europe, prehistoric artists and craftsmen, a princess who gave the mountains their name, a future king of France, and technicians working for the Luftwaffe.

The photograph shows the upstream/main entrance to the Grotte de Mas d’Azil. This is one of the few caves in the world that has given its name to a Stone Age culture – the Azilian. Thanks to its twin entrances, a road was built through the cave in the 1850s, and modern travellers can enjoy a unique prehistoric drive-through experience.

Herders on the Move

Seasonal grazing of high mountain pastures has been one of the defining characteristics of the Pyrenean way of life since it was introduced by agro-pastoral immigrants 7,000 years ago. Today, it is a peaceful occupation, but its history includes bloody conflicts between warring shepherds and confrontations with marauding bears. Only when it had almost died out did people begin to realise the role migrating livestock have played in shaping the Pyrenean environment, and the role these animals can still play today.

After a summer in the high mountains, the flock in this photograph prepares for the long walk home from Lac d’Estaing in the French Pyrenees to the home farm near Bordeaux. It will take them three weeks to complete this journey of 340 kilometres, or roughly the same distance as London to Manchester or New York to Washington DC.

Shaping the Environment

Since the first farmers reached the Pyrenees 7,000 years ago, human activity has been the principal factor modifying the landscape. Starting in the 1990s, pollen studies have allowed us to sketch a picture of the ebb and flow of the forest over the millennia, a dynamic that was mainly driven by farmers creating new agricultural land, metal industries consuming charcoal, and cities seeking construction materials. More surprisingly, the king’s navy also had a dramatic effect on forests on the northern slopes of the Pyrenees. As for the slopes themselves, whole communities came together to terrace vast swathes of Pyrenean hillside. This Herculean labour allowed people to survive at altitude, but due to mechanisation, nearly all the ancient terraces were suddenly abandoned in the 1960s. A notable exception are the vineyard terraces of the Banyuls-Collioure wine appellation on the Mediterranean coast, shown in this photograph.

Home Sweet Home

The first cities in and around the Pyrenees were built by Iberian tribes or Greek and Roman colonists. Frequently, their ancient foundations have been discovered because of modern house-building projects, with one particularly curious example being located on a Spanish island marooned in the French Pyrenees. Our contemporary appetite for second homes has saved some mountain communities from extinction and created others from scratch, but only one Pyrenean valley has seen an explosion in its permanent population. After 7,000 years of sheep rearing and forestry, Andorra found a way to transform itself into a nation that attracts more tourists per head than any other country in the world.

This photograph comes from a 1920s postcard. A youthful postman rides one of four mules carrying the mail uphill from La Seu d’Urgell to Andorra-la-Vella. This rustic way of life persisted until Andorra began a rapid transformation in the second half of the 20th century.

Signs of Worship

The religious history of the Pyrenees is far more complex and diverse than the ubiquitous signs of Christianity might suggest. Starting with Neolithic farmers, successive waves of newcomers introduced a wide range of beliefs to the mountains. As a result, notable signs of worship include: a megalithic tomb which provides an unparalleled example of prehistoric recycling; votive altars from the Roman period which hint at the relationship between the old and the new gods; fresh archaeological discoveries which shed light on the chaotic period when the Pyrenees were at the heart of the largest state in western Europe and Christianity was trying to establish a foothold in the mountains.

In the Pyrenees, you are rarely far from a megalithic monument. Some ancient tombs are so eye-catching, they seem deliberately designed for display. To create the Dolmen de Gasteynia (shown in the photograph), its builders raised an artificial mound 2 metres high and 40 metres in diameter, and then they dragged the capstone across from the other side of the valley.

On the Front Line

Throughout history, security has called for fortifications, and the Pyrenees are no exception. This section focuses on four main periods: the 8th century, when Christians and Muslims fought against and alongside each other on both sides of the Pyrenees; the 12th century, when the counts of Foix created a unique network of fortifications using natural features of the Ariège valley; the 17th century, when a treaty moved the Franco-Spanish frontier 40 kilometres southwards; the 20th century, when the Germans fortified one side of the Pyrenees and Franco began building 10,000 bunkers on the other.

The photograph shows two of Franco’s anti-tank bunkers near the south entrance of the Vielha tunnel in the Spanish Pyrenees. These are among the highest fortifications in the whole Pyrenean line, and they date from 1944.

Rich in Minerals

Starting in Roman times, Pyrenean quarries have produced more than 150 different types of marble. In the early 20th century, the Mines of Bulard (shown in the photograph) contained the highest galleries in Europe, so cold they were permanent ice caves, so dangerous they were known as the Man-Eater. More recently, the site has been given a more appealing name: the Machu Picchu of the Pyrenees. Mineral water springs have left an even greater mark on the Pyrenees. Although exploited by the Romans, their influence peaked in the 19th century when, combined with the arrival of the railways, spa towns helped attract more people to the Pyrenees than ever before.