From brigand to metal-basher: explore the copper industry of Durfort

My previous article about the fortified village of Castlar finished with a question: why did the population leave a safe and sunny hillside to live down by a gloomy river? (click here if you missed it: PREVIOUS ARTICLE).

One reader suggested two possibilities: (i) after the fire had destroyed their granary, the inhabitants of Castlar realised it might be sensible to be closer to a major source of water (ii) times had changed and there was less need to live inside defensive fortifications.

BAD NEIGHBOURS CAN BE GOOD NEIGHBOURS

The second possibility is particularly intriguing because at around the same, a band of brigands moved into another fortified settlement called Roquefort, a mere two kilometres upstream of Castlar.

After the fall of Carcassonne in 1209, Roquefort (no connection with the cheese) had provided a refuge for 300 Cathar faithful. Then, starting in the 1370s, it became the hideout of one of les Grandes Compagnies, or Free Companies, which plagued France throughout the Middle Ages. These were bands of mercenaries who fought for both sides during the Hundred Years War, but when they were dismissed during the brief intervals of peace, they devoted themselves to private plunder. At Roquefort, the brigands set up permanent home, staying there for 40 years. Any merchant who travelled through the area had to pay a levy or risk forfeiting his wares and his life. Nearly all the towns and villages in the surrounding countryside as far as Carcassonne and Toulouse had to buy off the plunderers – in some cases several times – or risk destruction.

With such unpleasant neighbours on their doorstep, why did the people of Castlar decide this would be a good time to abandon the safety of their walled settlement? This is the type of situation in which history becomes particularly fascinating. In the absence of any contemporary documents to enlighten us, all the history lover or professional historian can do is speculate. For example, perhaps the brigands of Roquefort were so busy robbing and ransoming the wider region, they had no time to produce their own food. Perhaps they struck a deal with their neighbours at Castlar: provide us with rabbit, rye, broad beans and grapes, and we’ll protect you (my previous article explains this strange combination of foodstuffs). Given their fearsome reputation, this would have been a copper-bottomed security guarantee.

Other communities in the surrounding area tried bribing the brigands to go elsewhere, without success. In 1415, the king ordered his lieutenants to clear them out by force, but the following year they rolled back into Roquefort like a pocketful of bad pennies. The king’s men evicted them a second time, and realised the only way to stop the brigands coming back was to destroy Roquefort, bringing an end to four decades of nefarious activity.

Forty years in one place is a long time for anyone. Even for brigands, it is certainly long enough to put down roots, long enough to marry a local girl, long enough to start a family, long enough to have grandchildren. This thought has led to a suggestion by local historians that, after their final eviction, some of the outlaws settled in the new village of Durfort where they took to beating seven bells out of pieces of copper instead of passing travellers.

A COPPER BOTTOMED BUSINESS

As early as the mid-13th century, the power of the Sor at Durfort had been used to grind wheat and produce textiles, but following the abandonment of Castlar and the destruction of Roquefort, the focus of those harnessing hydraulic power switched to metal, particularly copper. There were no copper mines in the vicinity, so the people of Durfort melted down other people’s scrap and poured the molten metal into clay moulds to form discs the size of a thick pizza.

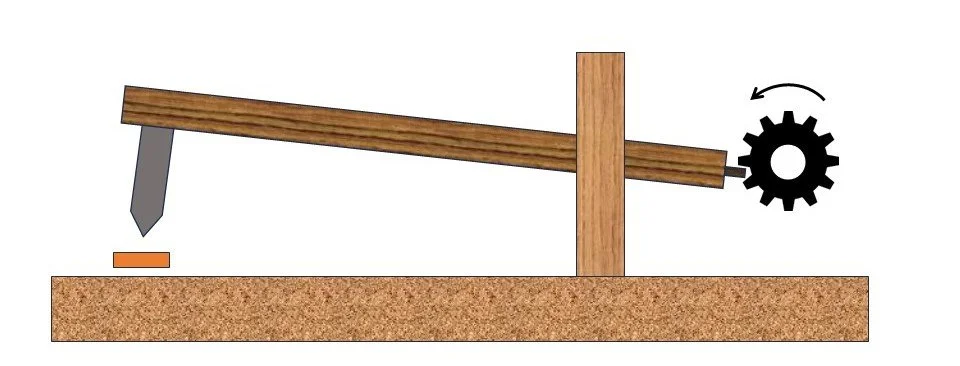

These discs were then bashed into shape using the hydraulic trip hammer, a type of machine which had appeared in medieval France during the 12th century. Imagine a horizontal wooden beam pivoted about three-quarters of the way along its length. Attached to the end furthest from the pivot is a metal hammer weighing around 250 kilograms. At the other, a gearwheel powered by the flow of the river presses down on the beam and lifts the hammer at the far end by 20 centimetres. Between each click of the cog, the hammer falls, applying one-and-a-half tonnes of pressure 150 times minute.

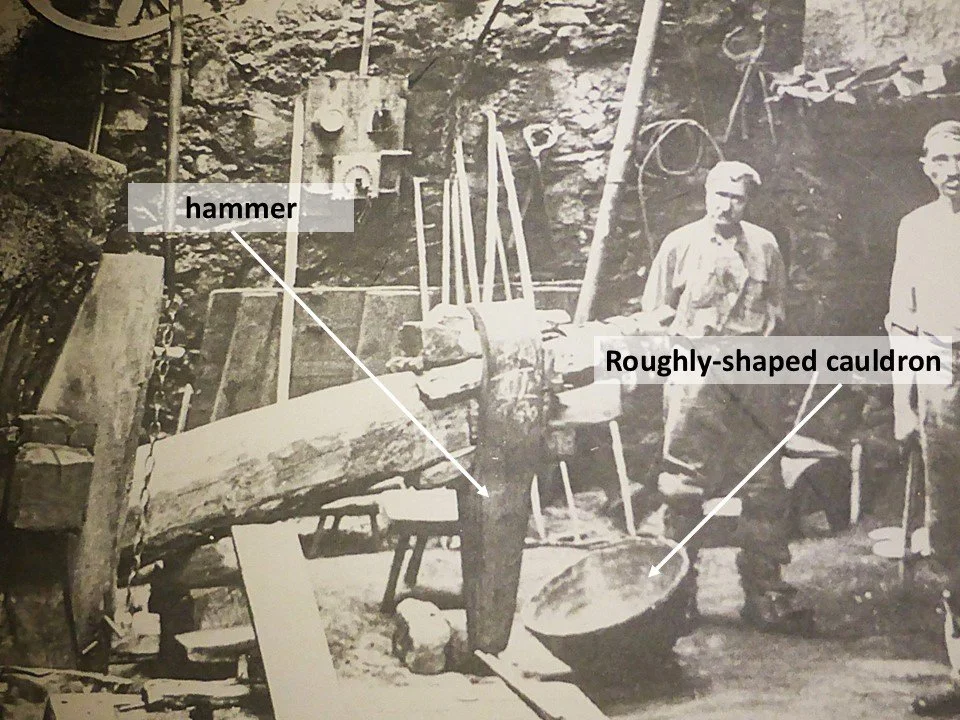

This massive force allowed the maître martineur to shape the copper disks into rough receptacles (the English translation – master trip hammer operator – doesn’t quite have the same ring to it, does it?) At Durfort’s peak, there were 38 mills powering trip hammers in 3.5 kilometres of river upstream of the village.

The next stage of copper-working took place in the houses and streets of Durfort where 500 cauldron-makers banged away for twelve hours a day. They hardened the copper by beating it, riveted on a handle or two and strengthened the vessel by rolling the lip around a thin iron hoop.

KNOCK OUT BLOWS

Today, the loudest noise in Durfort is the rush of the river or the howl of a wind called the vent d’autan. In these quiet streets it is almost impossible to imagine the infernal din that used to fill this valley 12 hours a day, six days a week. At the end of the nineteenth century, a doctor noted that deafness was common among the workers, and that such long contact with copper caused their forearms and hair to take on a greenish tinge and their gums to turn reddish-brown.

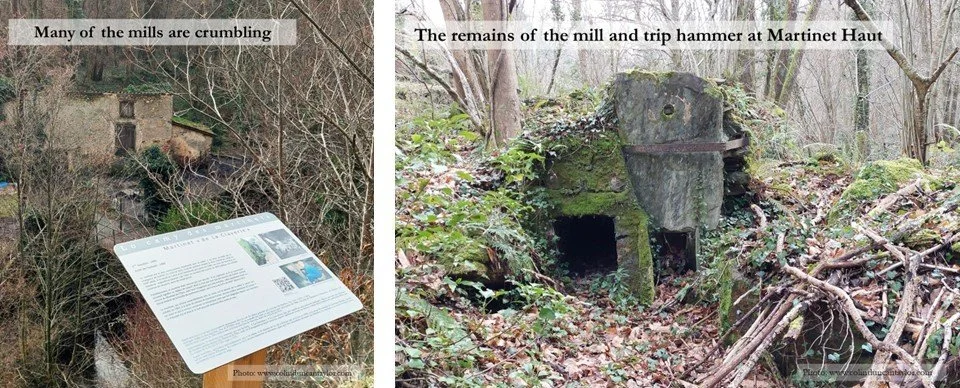

In the 20th century, two world wars and a flood brought the industry to its knees. By 1943, there were only four trip hammers still operating, and people with the skills to operate them were scarcer still. During the inter-war years, mill owners had gone to Italy in search of maîtres martineurs. Then, in 1948, one of these Italian settlers recruited a 14-year-old nephew called Giordano Ferrari. When Giordano retired in 1993, the last of Durfort’s mills closed its doors. Giordano Ferrari was the last practitioner of his profession in the whole of Europe.

Some of my older neighbours remember Durfort in its heyday. On Sundays, the town was packed with people from the surrounding towns and cities coming in search of copper utensils. Today, one or two shops still offer traditional wares, and a copper vessel hangs outside nearly every house. There is also a small museum devoted to copper, but best of all are the 20-or-so information boards erected last year by the village council along the 3.5 kilometres of river where the trip hammers once thumped out their rhythmical beat.