Astonishing tales from the earliest days of French aviation

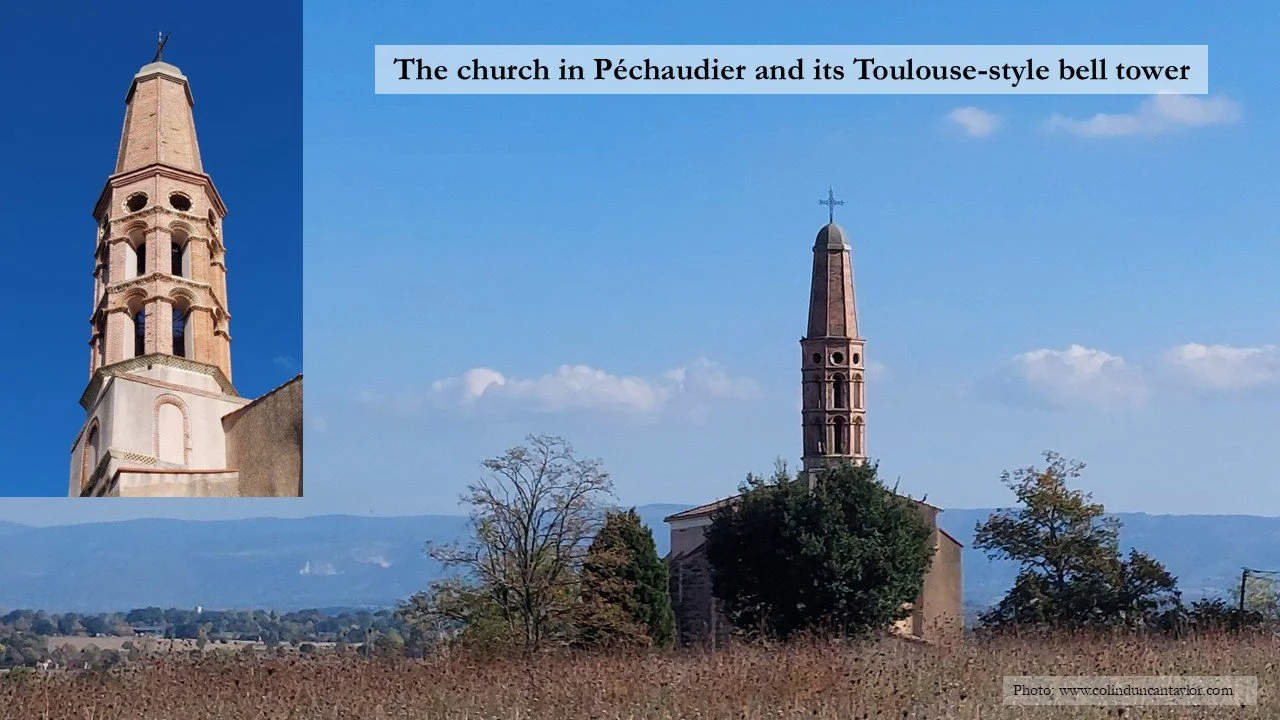

Péchaudier in the south of France is blessed with a pretty little church. For no obvious reason, it stands alone in open fields a kilometre outside its village. Viewed against the backdrop of the Montagne Noire, its 16th-century bell tower is particularly striking. Such a tranquil church seems an unlikely place for a teenager to build an aeroplane, particularly in 1910 when powered flight had barely reached Europe. His subsequent career makes an even more unlikely tale.

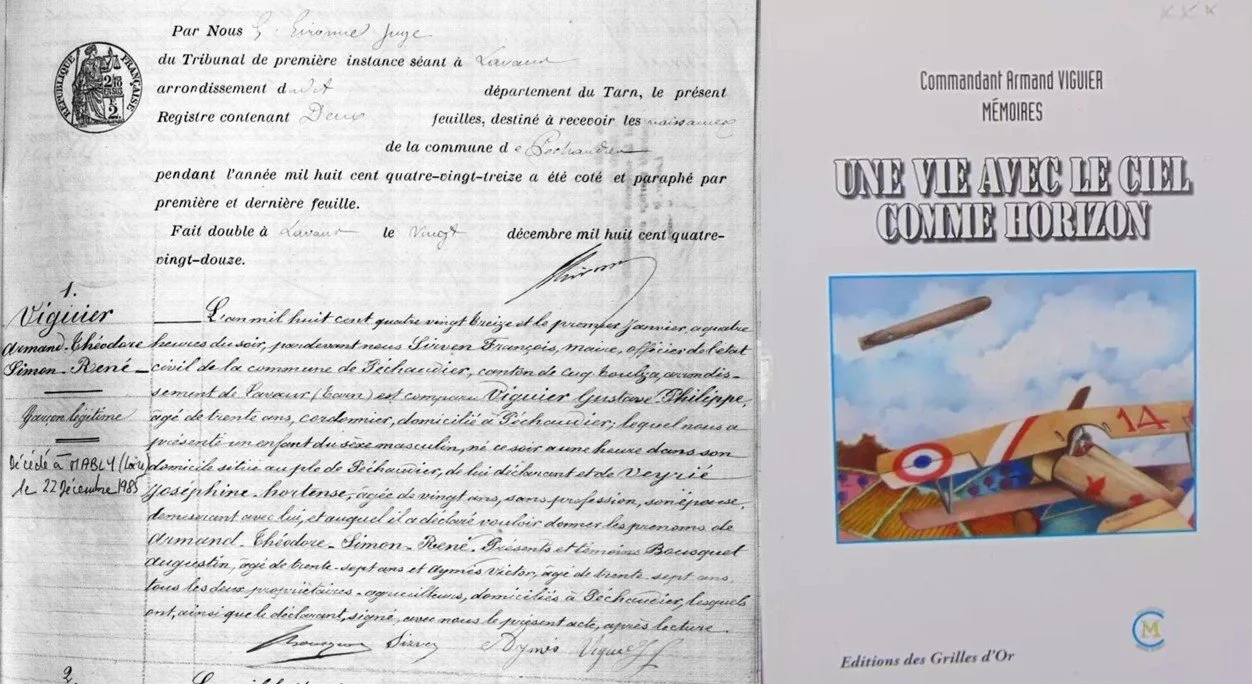

Armand Viguier was born in Péchaudier in 1893, the son of a cobbler. My village is next door, and I discovered Armand’s story while drinking beer at my village fête this summer. One of my neighbours is a retired airline pilot and he is always ready to share aviation stories, the older the better.

POWERED FLIGHT REACHES FRANCE

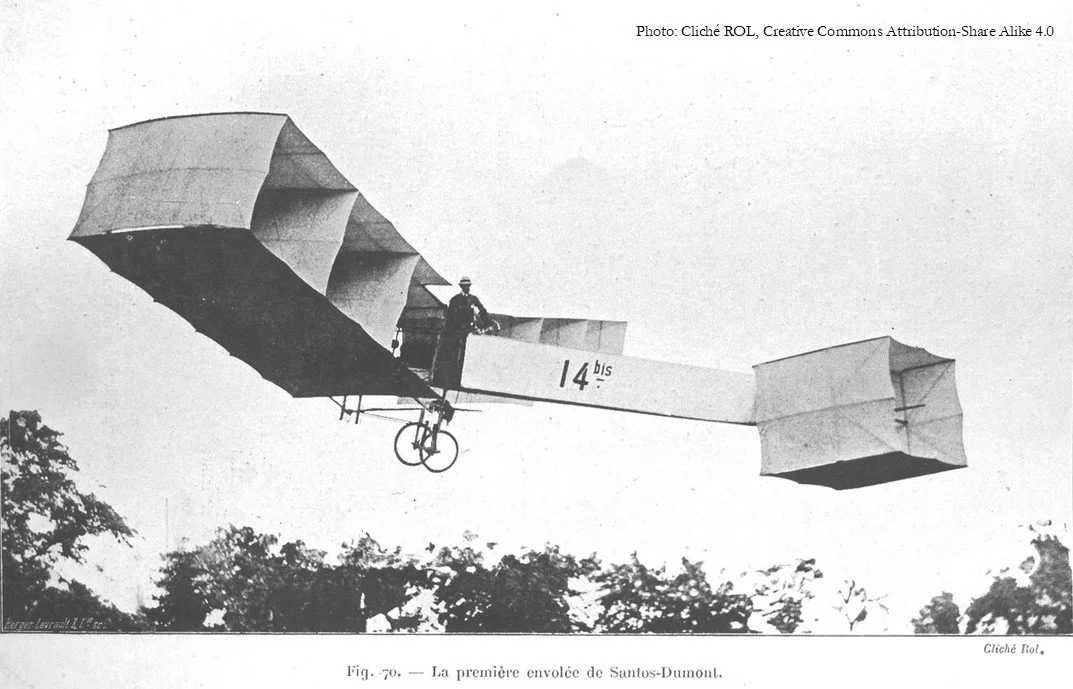

Le Grand Prix d'Aviation was a prize created in France in 1904, only a few months after the Wright Brothers had made their historic first flight in the United States. Fifty thousand French francs (equivalent to around €125,000 today) would be awarded to the first pilot who could make a circuit of at least one kilometre in a machine heavier than air. Early progress was painfully slow. For example, on 13 September 1906 a crowd gathered near Paris hoping to see a prize-winning flight by the Brazilian aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont. His aircraft was French – a 14-bis. It failed to take off the first time, but on its second attempt, it flew for a distance of somewhere between 4 and 7 metres at a heady altitude of 70 centimetres! Le Grand Prix d'Aviation was eventually won in January 1908.

FLY ME TO HEAVEN?

Most of these early French aircraft were manufactured and flown in or around Paris, but tales of their exploits spread far and wide and even reached the village of Péchaudier where they inspired Armand Viguier to embark on an unusual project. Starting in 1910, he built a life-size pedal-powered aeroplane. His enthusiasm for aviation seems to have been shared by the village priest, Abbé Causse, because Armand was allowed to use the church as his workshop. Perhaps the priest imagined this strange craft would carry him and his parishioners closer to God. There is no record of it ever leaving the ground.

CAVALRYMAN, MECHANIC, PILOT

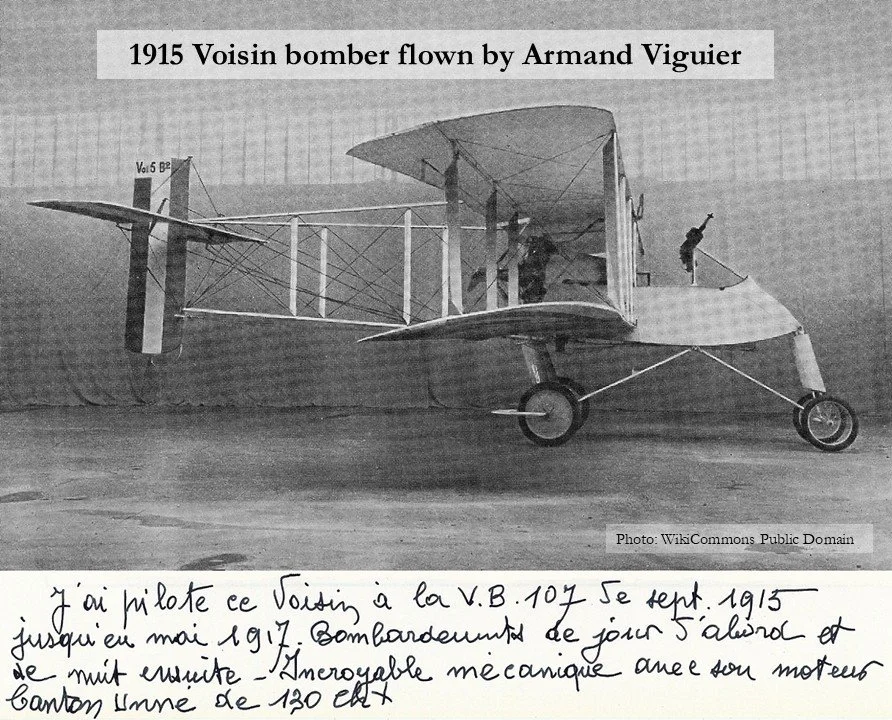

In 1913 Armand forgot about flying and enlisted in the 10th Dragoons, a cavalry regiment based north of Toulouse in Montauban. A year later, he trotted off to war. In September 1914, he survived taking part in a cavalry charge against German machine guns, but his horse did not. In fact, his regiment lost over a hundred horses in those early days of the war and Armand was sent back to Montauban where he set about training new horses purchased from Canada. He also resumed dreaming about aeroplanes. That winter, he built another one. Perhaps his aeronautical skills and enthusiasm impressed his superiors because, in March 1915, they approved his request to become a trainee mechanic in the air force. In June of the same year, he became a trainee pilot, and after one month’s instruction, he was flying a Voisin biplane. It might not look like a bomber to us, but that was indeed its role.

In his handwritten caption, Armand Viguier tells us, ‘I piloted this Voisin in the VB 107 squadron from September 1915 to May 1917. First we bombed by day, then by night. Incredible mechanics with its 135 horsepower Canton-Unné engine.

FORCED LANDING, CRASH LANDING

His first mission ended with a forced landing in a field of cows, luckily on the French side of the lines. A year later, he crashed and broke a leg. By now, the Voisin was proving increasingly vulnerable to attack by German aircraft which is why the squadron switched to bombing by night. In 1917, mechanical failure led to another crash and another injury. After convalescing, he asked to switch to fighters and spent the rest of the war flying Spad VIIs and Spad VIIIs.

FROM FIGHTER PILOT TO AIRBASE COMMANDANT

As soon as he entered active service with his first fighter squadron, he shot down an enemy aircraft. According to Armand, his commandant told him it was unacceptable for an ex-bomber pilot to turn up and shoot down an enemy plane just like that. His victory was awarded to another pilot. Over the next year, he shot down four more enemy aircraft, for which he received due recognition.

The signing of the Armistice on 11 November 1918 did nothing to dampen Armand’s passion for flying. He stayed on in the air force and by the time France surrendered early in the Second World War, he was commandant of the Lyon-Bron airbase.

As you will see from the handwritten note on his birth certificate, this daring aviator died peacefully in 1985 at the age of 92. Throughout his long career, he had kept a diary, and his son turned these intimate notes into a book published in 2007: ‘Une vie avec le ciel comme horizon’ or ‘A life with the sky as a horizon’. It makes a fitting tribute to a pioneering spirit from the earliest days of aviation.